Since time immemorial, conquest has determined who occupies a land and who does not.

Territory has never been distributed by moral abstraction or granted by retrospective entitlement, except in recent times and only in the Western world.

Land has always been claimed, defended, and passed down by force, will, and continuity. This law has governed the movements of peoples across all centuries—whether in the slow drift of tribal migration or the shock of imperial expansion.

What is changing today is not the nature of conquest, but how it is remembered.

The phrase “stolen land” is an attempt to deny this reality. No phrase is repeated more casually and with less scrutiny. It appears in classrooms, on protest signs, and in official proclamations, as if it were a self-evident truth rather than a political invention designed to invert the meaning of history. The concept does not clarify the past. It repurposes it, weaponizing memory to serve the ideological needs of the present.

It is not a description of historical events but a formula of accusation, crafted to transform conquest into guilt and settlement into sin. It replaces historical understanding with a fixed moral narrative, one that justifies grievance in the name of justice and demands erasure in the name of memory. It recasts the builders of civilization as intruders and the victors of history as thieves.

In this framework, the phrase does not describe a border conflict or a military loss. It signifies the permanent illegitimacy of the victor, and it is applied exclusively to the descendants of European conquerors. This moral fiction now governs how the American Southwest is remembered and stands as the chief rhetorical obstacle to any serious defense of the civilization built there.

Its function is not merely retrospective. The myth prepares the ground for demographic transformation by denying the moral legitimacy of existing populations. If White Americans are portrayed as permanent usurpers, then their replacement is not a tragedy but a correction. This is the logic that underlies the narrative: that those who built must step aside for those who did not, because presence without ancestry is less offensive than ancestry without permission.

When we first confronted this accusation in relation to Mexico, we did so to refute the claim that the lands of Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California were wrongfully taken from a rightful Mexican inheritance. But Mexico’s claim was itself the outcome of Spanish conquest, built upon the ruins of earlier tribal orders. Its northern territories were weakly held, sparsely populated, and barely governed. They were frontier zones raided by hostile tribes, economically stagnant, and only loosely tethered to the Mexican core. Their absorption by the United States was not theft. It was consolidation, an act of settlement and struggle.

Even this, however, grants too much to the premise. The Mexican framing is merely the outermost layer of a larger ideological assault. The “stolen land” myth is not confined to the American Southwest, nor to the United States. It is a global narrative applied to every White-settled nation, from Canada to Australia, from former Rhodesia to South Africa, and always in the same pattern.

What is at stake is not the justice of one war or the boundaries of one treaty, but the legitimacy of the European presence in the New World and beyond. The purpose of this myth is to strip White nations of any rightful claim to the lands they built, casting their very existence as a permanent crime. It recasts founding as theft, inheritance as injustice, and continuity as illegitimate occupation.

The term “indigenous” serves as the instrument of that erasure. It offers a moral absolute: a group that arrived first, suffered most, and never recovered. This label, though applied globally, acquires its most weaponized form in the context of Western settler nations, where European peoples are not treated as builders of order but as trespassers without end. In this narrative, to be White is not to belong to a civilization but to an intergenerational invasion. The word “indigenous” functions as a replacement for historical understanding. It flattens the layered realities of migration, war, and succession into a binary of oppressor and oppressed, belonging and exile.

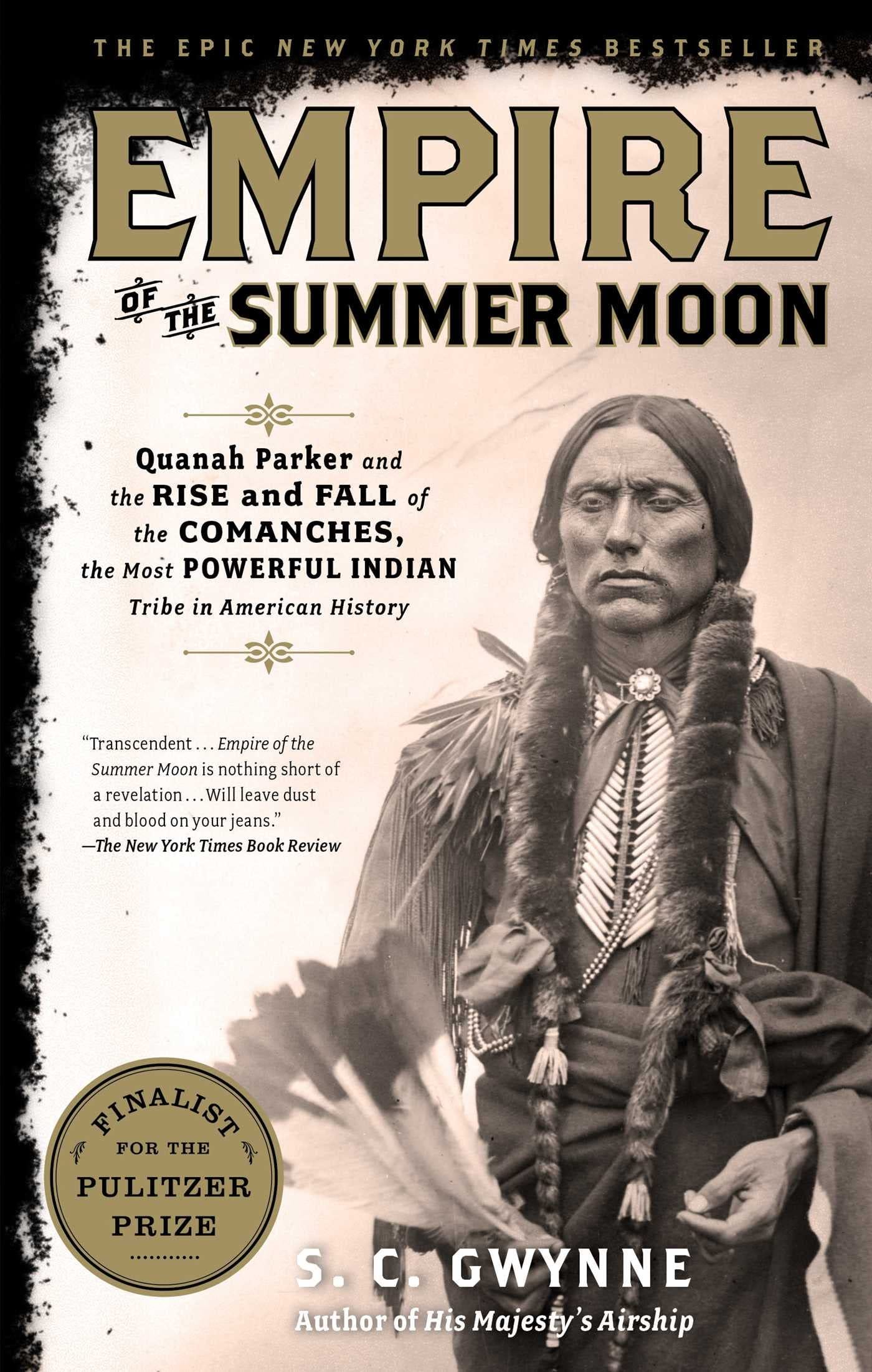

Yet there is no serious historical basis for this purity. The lands of the American Southwest were not stolen from a single indigenous nation. They were claimed from nature by many peoples in succession, most of them by war. The Comanche, whose empire is vividly documented in S. C. Gwynne’s Empire of the Summer Moon, were not gentle caretakers of sacred land. They were one of the most violent, expansionist, and militarily sophisticated tribes ever to roam the plains.

They displaced other Indians, raided deep into Mexico, trafficked in captives, and held vast territory through fear and predation. Comanche war bands tortured prisoners, gang-raped captured women, mutilated corpses, and slaughtered settlers without mercy. They burned homesteads, butchered children, and left mutilated bodies on the plains as a warning to others. Their authority was not symbolic, but absolute, imposed through terror and the complete subjugation of rival tribes. Their defeat at the hands of American settlers was not a moral tragedy but the outcome of a civilizational collision in which both sides understood the stakes. Territory belongs to those who can take it and hold it.

The same was true in California, where tribal fragmentation, ecological exploitation, and endemic violence defined the pre-contact world. The romantic image of peaceful tribal communities living in ecological harmony cannot withstand the scrutiny of serious anthropology. Robert Whelan, in Wild in the Woods, traces the noble savage myth to Renaissance projections and Enlightenment fantasies, not to historical accounts. From the earliest Spanish reports, we find widespread evidence of ritual cannibalism, enslavement, and infanticide among the peoples who now serve as icons of environmental sanctity. The illusion of indigenous innocence is not native to them. It is a European invention, shaped not by truth but by a manufactured guilt that distorts the past to indict the present.

Even the ecological argument—so often deployed to elevate indigenous societies as models of sustainability—collapses under scrutiny. Where scarcity imposed restraint, practices of conservation emerged, but these were not ethical principles; they were strategies of survival. As Allyn Stearman shows in Yuqui: Forest Nomads in a Changing World, her research on Amazonian societies reveals that when abundance returned, restraint disappeared. There were no sacred taboos preventing overhunting in the rich lowlands of Bolivia. What modern environmentalists call wisdom was, in most cases, merely necessity. And when necessity no longer applied, so too vanished the balance.

If we are to take history seriously, then we must dispense with these illusions. Violence and territorial conquest were not introduced to the Americas by Europeans. They were already present, embedded in tribal life, ritual structure, and myth. Among the Māori of New Zealand, slavery and cannibalism were institutional. In the Congo, children were captured, butchered, and consumed, not in famine, but as spectacle and assertion of power. In the Americas, the Maya conducted mass human sacrifices to celestial gods, and the Comanche burned men alive for sport and honor. These were not exceptional acts. They were structural practices. And to excuse them is not to respect indigenous cultures, but to infantilize them.

This is the ultimate consequence of the “indigenous” framework. It denies to non-Western peoples the full moral agency that we expect of ourselves. It absolves them of the duties of judgment, responsibility, and consequence. It recasts them as eternal victims, existing not in history but in myth, useful only as moral leverage against the civilization that outcompeted them. This is not scholarship, but a form of ritual abasement that calls not for understanding, but for surrender.

There is no reason to participate in this fiction. The American Southwest was not stolen. It was conquered, built, and defended. And conquest is not a sin. It is a historical constant. Every people that now claims a homeland has done so by seizing it from others or preserving it through resistance. The Comanche understood this. So did the Spanish, and so did the Americans. What is unique to our time is the expectation that we forget it, that we dissolve the foundations of our own legitimacy in order to appease the descendants of those who, given the opportunity, would not have hesitated to do the same.

In practice, the “indigenous” framework serves to justify the displacement of White populations under the guise of moral restitution. It allows demographic revolution to proceed not as conquest but as redemption. Erasure becomes a virtue, so long as it is inflicted upon the builders of the world they now inhabit.

To reject this demand is not to deny the past but to remember it fully, and to affirm the right of White peoples to endure as the stewards of their own civilization. The truth may be unwelcome to those who profit from our disappearance. But it remains ours to defend. It is the inheritance of our ancestors and the birthright of our posterity.

It's why as much as I detest the State of Israel I don't use "stolen land" rhetoric against them; if they can conquer the Palestinians, it's their land.

If savages (and our primary enemies who are enabling them) can re-take America and remove me from my own home without me being able to stop them, they have earned it. The problem is our people forgot this and are still making legal arguments hoping invaders and bandits can be persuaded.

Force is all that matters, "property rights" and constitutions are gentlemen's agreements on already conquered and defended land.

Two wolves fighting over territory don't debate right and wrong, or who's the rightful owner of anything. This is the underlying barbarism of reality that much of the world is already in the mindset of that decadent people thought we somehow progressed out of.

Whoever can conquer, is the heroic victor. Moral arguments have their place within civilizations among countrymen, but don't really matter in war.

In other words, it's time for the White man to conquer, and be the fucking "bad guy."

An excellent piece, Mr. Crowley! I discovered your excellent Substack yesterday and read your piece on how the American Southwest was NOT stolen. I will admit that I don’t always agree with your views but I nonetheless have great respect for you and that you challenge politically correct historic myths that everyone these days just takes as gospel. I also wanted to mention you may not agree with everything I write in my comment here either but I hope you will give me a fair hearing because I think you make an excellent point here.

Indeed there is a BIG difference between conquered and stolen. But white Europeans and Americans did NOT steal the Americas from its Indigenous people they conquered them in war often with the help of other indigenous peoples. For example, the Tlaxcalans assisted the Spanish in fighting and defeating the Aztec Empire and helped Spain to conquer the Philippines. Columbus and his men were assisted by the Tainos in fighting the Caribs. General George A. Custer had Kiowa scouts assisting him and the U.S. Army in fighting the Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho. Just to name a few examples. It’s not like the Indigenous people all liked each other. Each tribe was a nation unto itself and they fought each other in bloody wars and conquered each other’s land long before and long after the white man showed up on the continent. The Chickasaw and others drove the Sioux from their native lands in Minnesota.

The Sioux then conquered and massacred the Ponca, Oto, Kiowa, Omaha, and Pawnee without mercy and took their lands. The land in the Black Hills where Mount Rushmore currently stands? The United States took it from the Sioux who had previously taken it from the Cheyenne who had previously taken it from the Crow. Conquest is just a part of human history and they did it to each other all the time. The Native Americans were not idyllic hippies who spent all day dancing and lived in a pristine utopia until the white man came along and ruined everything. They practiced not only conquest and fought wars but also practiced human sacrifice, cannibalism, head hunting, chattel slavery, sexual slavery, environment destruction, and torture of prisoners.

Yes, there are individual cases where white settlers through chicanery and trickery stole land from Natives and that was of course wrong. But most of the land in this country was acquired via conquest or in peaceful trade with the Native peoples. By the way, conquest has been the norm throughout human history until it’s formal reputation in 1949. But for most of human history if you had the military strength to take and hold a piece of land you got to keep it. The Indigenous peoples of the Americas are far from the only ones who that happened to and they did it to each other all the time. Indigenous peoples around the globe like the Aboriginal Australians, the Māoris and the Native Hawaiians were not angels who spent all their time holding hands and singing kumbaya before the Europeans arrived.

The Nobel Savage trope is complete nonsense and if you truly want to respect Indigenous cultures and people and not infantilize them you need to stop repeating these myths. There are many other examples of conquest from history I can think of where it would just as ridiculous to claim the land was stolen. The English conquered the Scots and the Irish, African tribes conquered and enslaved each other, the Romans brutally took over Gaul and massacred one million of its people, the Japanese brutally tyrannized over the Chinese, Vietnamese, Koreans, Filipinos, Indonesians, and Burmese, the Haitians took control and ruled over the Dominicans, so on and so forth. The Comanche Empire and the way they ruthlessly took the land of other Native American tribes shows that the Native people were just as land hungry, greedy and power hungry as any other group of people. No, America is not a stolen country and this myth is absolutely ahistorical and ridiculous. I recognize the grave injustices done to the Native Americans by the U.S. government. But they don’t change the fact that the things that happened between white settlers and the Indigenous people is the same things that human beings have done to each other for over a millennia.