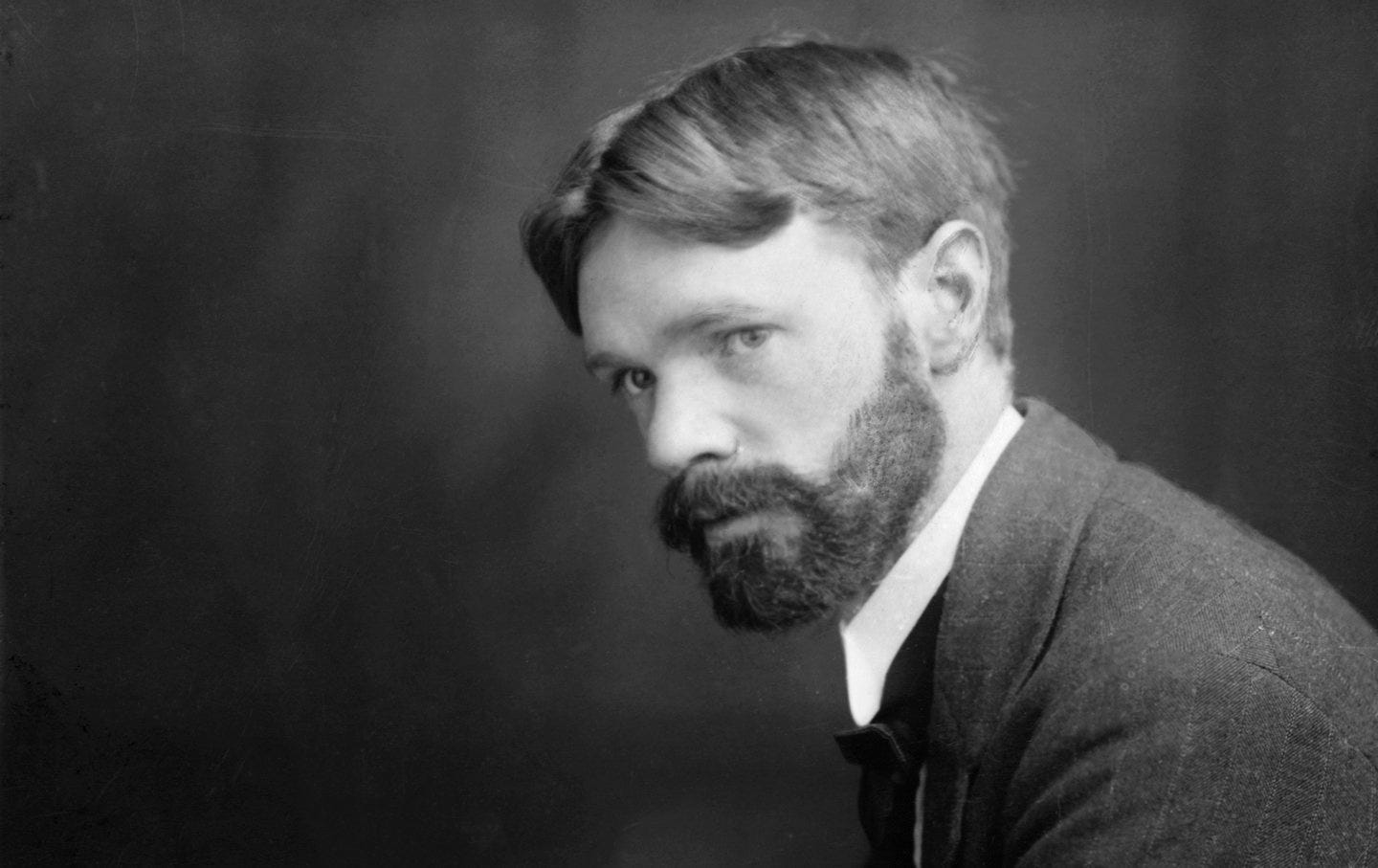

David Herbert Lawrence (1885–1930), known to posterity as D. H. Lawrence, was an English novelist, poet, and essayist whose critique of modernity and celebration of life’s vitality remain unparalleled. Born in the industrial mining town of Eastwood, Nottinghamshire, Lawrence was acutely aware of the estrangement between man and nature brought about by industrialization. His philosophy revolved around what he called “blood consciousness,” a term he used to describe the intuitive, primal wisdom of the body and instincts—a wisdom he believed superior to the abstract reasoning of the intellect.

Lawrence’s works embody this vision of life. “My great religion,” he declared, “is a belief in the blood, as the flesh being wiser than the intellect.” For Lawrence, the intellect had become a tyrant, severing mankind from the vital instincts of the blood—the true source of life and meaning. His writing sought to restore this connection, not as a nostalgic return to the past, but as a recognition of the enduring forces that sustain existence. Blood consciousness, for Lawrence, was not simply a biological reality but an elemental awareness that grounded man in the rhythms of the natural world. “We can go wrong in our minds,” he wrote, “but what our blood feels and believes and says is always true.” The intellect, while useful, was secondary—a force prone to distortion when untethered from the deeper truths of the flesh.

For Lawrence, life was not merely a biological process but the irreducible, primordial force underlying all existence. It was not something to be dissected or fully comprehended but an inexplicable primary that modern science, with its obsession for categorization, failed to grasp. Lawrence dismissed the notion of an immaterial, disembodied spirit, asserting instead that the living and the material were inseparable. In The Two Principles, he claimed, “Inanimate matter is released from the dead body of the world’s creatures. It is the static residue of the living conscious plasm, like feathers of birds.” For Lawrence, even the inanimate universe was born of life—its decomposed remains. Death, for him, was not a negation but a transformative process, returning living energies to the earth and fueling the eternal renewal of existence.

This vision extended to Lawrence’s conception of origins, though he approached it less as literal fact and more as a mythic expression of life’s creative mystery. In A Study of Thomas Hardy, he described a hypothetical “great unmoved, utterly homogeneous infinity” that represented the undifferentiated beginning of life. He admitted that this vision was symbolic, not scientific, noting elsewhere that there never was a single starting point for existence. Instead, this notion of a primordial unity served as a metaphor for the inexhaustible vitality that drives the cosmos. For Lawrence, this mystery of creation, akin to Schopenhauer’s “will,” perpetually manifests itself through individual beings. He likened the dissolution of the self at death to rain returning to the sea, writing, “When we die, like rain-drops falling back again into the sea, we fall back into the big, shimmering sea of unorganized life which we call God.”

The individual, for Lawrence, was not merely a fleeting expression of this life force but its very essence. He rejected abstract notions of collective or universal life, insisting instead on the primacy of individuality. In Fantasia of the Unconscious, he declared, “Life is individual, always was individual, and always will be.” For Lawrence, every living being was a unique and irreplaceable manifestation of the creative mystery, its existence defined by its unrepeatable character. He saw the soul not as a product of something external but as the origin of all things. “The individual soul originated everything, and has itself no origin,” he wrote, underscoring his belief that life’s mystery resides in the singularity of individual existence.

This creative mystery, which Lawrence sometimes described as the “Holy Ghost,” acted as the force that reconciles life’s dualities—light and dark, life and death, fire and water. For Lawrence, the Holy Ghost was the principle that allowed life to flourish by holding opposing forces in balance. In Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine, he wrote, “In the seed of the dandelion, as it floats with its little umbrella of hairs, sits the Holy Ghost in tiny compass. The Holy Ghost is that which holds the light and the dark, the day and the night, the wet and the sunny, united in one little clue.” This metaphor captured Lawrence’s vision of life as a dynamic interplay of opposites, with every living thing embodying the eternal tension and harmony between them. For him, individuation was not a solitary act but a continuous process of balancing and integrating these polarities.

Lawrence’s metaphysics, steeped in this vision of individuation and balance, bore striking similarities to the philosophy of the Pre-Socratics, particularly their understanding of the cosmos as a dynamic, living process. Like Anaximander’s apeiron—the boundless, indeterminate source from which all things emerge and to which they return—Lawrence saw existence as an eternal flux, an endless interplay of creation and dissolution. The apeiron represented an origin that was not fixed or knowable but inexhaustible, much like Lawrence’s shimmering sea of unorganized life. Both conceptualized the cosmos as a self-renewing system in which opposites constantly transformed into one another, sustaining life’s vitality.

This idea resonated deeply with Lawrence’s belief in the cyclical nature of existence. In Fantasia of the Unconscious, he described life as “propagation between two infinities,” a phrase that evokes Heraclitus’s notion of flux. For Heraclitus, the world was a continual process of becoming, defined by the unity of opposites. Fire, for example, simultaneously consumes and creates, embodying the tension that drives the cosmos. Similarly, Lawrence’s “Holy Ghost” served as the mediating force that reconciles dualities, ensuring that life does not stagnate but constantly moves forward in a dynamic process of individuation. He shared the Pre-Socratics’ rejection of static conceptions of being, insisting that vitality depends on this tension and transformation.

Lawrence’s emphasis on opposites also aligns with the Pre-Socratic concept of phusis, the natural principle of growth and change. For thinkers like Anaxagoras and Empedocles, phusis was not a passive state but an active force, driving the emergence and decay of forms in a continual cycle. Lawrence echoed this in his insistence that life’s essence lay in its contradictions. Light and dark, fire and water, life and death—these polarities were not antagonistic but complementary, each necessary for the other’s existence. The dynamic balance of these opposites was, for Lawrence, the secret to life’s creative power.

In drawing on these ancient ideas, Lawrence imbued his metaphysical vision with a profound sense of timelessness. His descriptions of the eternal flux of creation and dissolution, the interplay of opposites, and the ceaseless renewal of life echo the Pre-Socratics’ attempts to understand the cosmos not as a series of static forms but as a living, breathing reality. By aligning himself with this tradition, Lawrence positioned his philosophy as both a critique of modernity’s mechanistic worldview and a reaffirmation of the eternal rhythms that sustain existence.

This vision of life found vivid expression in Lawrence’s literary works. In Lady Chatterley’s Lover, he contrasted the mechanized sterility of modern life with the primal vitality embodied in the affair between Lady Chatterley and Mellors. Their relationship, for Lawrence, was more than a romantic or sexual encounter; it was a reclamation of life’s instincts, a return to the wisdom of the blood. “Sex is our deepest form of consciousness,” he wrote, asserting that physical intimacy was not merely a biological act but a profound means of reconnecting with the creative mystery. The novel’s central tension between mechanization and instinct mirrored Lawrence’s broader critique of modernity and its suppression of life’s primal rhythms.

Lawrence’s disdain for modernity extended beyond mechanization to its egalitarian ideals, which he regarded as a denial of life’s natural hierarchies. In Studies in Classic American Literature, he argued that America’s obsession with equality had led it to “push a pin right through its own body.” While political equality might be tolerable, he viewed social and intellectual equality as grotesque distortions of life’s natural order. For Lawrence, life thrives on difference, distinction, and hierarchy, not on the sameness imposed by democratic ideals. By rejecting natural inequality, modern society was, in his view, suffocating the forces that sustain vitality. He saw this leveling impulse as emblematic of a culture disconnected from the blood consciousness that celebrates individuality and the creative tension inherent in life.

Art, for Lawrence, was the antidote to this disconnection. He believed that its purpose was not aesthetic in the conventional sense but moral in its transformative power. “The essential function of art,” he wrote, “is a morality which changes the blood, rather than the mind.” For Lawrence, great art stirred the instincts, reawakening the primal awareness dulled by modernity’s abstractions. His novels, such as The Rainbow and Women in Love, vividly explore the alienation caused by the suppression of blood consciousness and the possibility of redemption through a return to life’s primal forces. These works do not offer tidy solutions but instead invite readers to confront the tension between instinct and intellect, individuality and collectivity, creation and dissolution. Through art, Lawrence sought to remind mankind of the dynamic, eternal rhythms that lie at the heart of existence.

In Women in Love, Lawrence gave voice to his metaphysical vision through the character of Birkin, who contemplates mankind’s place within the broader creative mystery of existence. “If mankind is destroyed, if our race is destroyed like Sodom, and there is this beautiful evening with the luminous land and trees, I am satisfied. That which informs it all is there, and can never be lost.” For Lawrence, the creative mystery was inexhaustible, a force that transcends the fragility of human life. Even the destruction of mankind would not extinguish the fountainhead of vitality that perpetually generates new forms of life and consciousness. This belief in the indestructible essence of creation underscores his rejection of despair; for Lawrence, life’s renewal is eternal, even if its manifestations are transient.

This inexhaustible force was not, for Lawrence, separate from the material world but deeply rooted in it. He rejected dualistic distinctions between body and spirit, seeing them as inseparable aspects of the same living reality. “God is the flame-life in all the universe,” he wrote, insisting that divinity is not an abstract, external force but the very vitality that animates existence. In The Man Who Died, Lawrence reimagined the resurrection of Christ not as a supernatural event but as a profound reawakening to this creative mystery. Christ, in Lawrence’s telling, becomes aware of the “raging destiny of life” that transcends death, embracing the eternal interplay of life and dissolution that defines existence. Through this reinterpretation, Lawrence offered a vision of spirituality rooted in the material and the immanent, a faith grounded in the rhythms of the blood and the cycles of life.

Ultimately, Lawrence’s philosophy was a call to embrace the fullness of life in all its contradictions. The wisdom of the blood, the creative mystery, and the Holy Ghost were not abstract concepts but vital forces that shaped every aspect of existence. For Lawrence, the suppression of these forces by modernity—through mechanization, egalitarianism, and intellectual abstraction—threatened to sever mankind from the very foundation of being. He believed that reconnecting with these primal rhythms was essential for the renewal of both the individual and society.

Through his novels, essays, and poetry, Lawrence sought to provoke this reconnection. His characters often struggle to navigate the tensions between instinct and reason, passion and control, freedom and belonging. They are not paragons of virtue but flawed, complex individuals grappling with the fundamental forces of life. In their struggles, Lawrence revealed his own search for balance, for a life lived in harmony with the blood’s wisdom and the creative rhythms of existence.

Lawrence’s vision was uncompromising. He rejected the sterility of modern life in favor of a worldview that celebrated vitality, individuality, and the eternal cycles of creation and dissolution. His works stand as a testament to his belief that life’s essence lies not in the intellect but in the instincts, not in abstraction but in the living, breathing reality of existence. In a world increasingly dominated by lifeless systems and mechanized progress, Lawrence’s voice remains a challenge—a call to rediscover the forces that make life meaningful, to awaken to the eternal rhythms of the blood.