A regime without purpose is a regime already in decay. A government that no longer knows what it exists to serve—only what it allows—has forfeited its claim to rule and surrendered itself to entropy. It may possess power, it may maintain the machinery of law, it may persist in appearance, but it no longer governs in any meaningful sense.

Across the Western world, the state has ceased to be an instrument of order and become instead a hollow mechanism, one that regulates without direction, that manages without belief, and that speaks fluently the language of rights, representation, and legality while offering in practice not leadership but compliance. The forms remain: elections are held, budgets are passed, decrees are issued—but these are rituals, not rulership. Governance has been reduced to the illusion of coordination, a theater of consensus sustained by debt, distraction, and the inertia of institutions that continue not out of conviction, but because the system itself has forgotten how to stop.

This is not the state as it was once understood. It is no longer polis or res publica, principate or republic, but something post-political—a managerial construct built from fragments, severed from tradition, rootless in identity, animated not by belief or destiny, but by the cold continuity of process. The modern West does not collapse from corruption in the classical sense, where private greed subverts public virtue; it dissolves from dissociation, from the severing of power from principle, of law from legitimacy, and of sovereignty from the will to preserve.

States that still possess wealth, weapons, and administrative capacity have lost the sense of what those things are for. Power is exercised without belief in its authority, wealth is hoarded without the discipline to create order, and even armies, vast and well-equipped, exist increasingly as theatrical symbols rather than instruments of national continuity. Sovereignty has not disappeared, but it has been transmuted into a kind of custodial function, no longer representing the imposition of order upon chaos, but the management of decay by caretakers of a process that no longer believes in itself.

What remains is not living leadership, but the decayed machinery of administration. It does not command, it reacts. It does not unify, it arbitrates. Rights are affirmed, but cut loose from obligation. Safety is promised, but without the strength or coherence necessary to uphold it. Law survives in form, but has lost its moral weight; justice, where it is still spoken of, is increasingly indistinguishable from compliance. What we call the state today is a body that has lost its animating spirit, a structure that moves, enforces, and even speaks, but cannot remember why it exists.

It is a state that multiplies laws because it cannot establish order, opens its borders not from confidence but from compulsion, and elevates a managerial class so deracinated from land, lineage, and history that it no longer conceives of governance as a civilizational task. There is no coordination of means and ends, no clarity of command, only a scattering of offices, lobbies, ministries, and procedural rituals that perform governance without exercising it. Ministries compete, legislatures stall, militaries posture abroad while their moral foundations erode at home, and the sovereign, no longer embodied, has become a ghost within the machine.

Nowhere is this disintegration more visible than in the contradictions of policy. We live under a regime that subsidizes demographic sterility while importing populations to replace its own, that disarms its citizens even as it arms foreign regimes, and that teaches children to despise their ancestry while prosecuting those who seek to preserve it. These are not aberrations, nor are they accidents. They are symptoms of a regime that no longer believes in its own right to exist, that cannot define the people in whose name it governs, and whose moral grammar now forbids even the asking of such a question.

Such a regime cannot be reformed, because its failure is not procedural. It is metaphysical. It no longer believes in order, in hierarchy, in continuity, or in the sacred bond between ruler and ruled. What remains cannot be preserved through nostalgia, nor redeemed through revolt. It must be outgrown, left behind like a dead skin, through the recovery of a deeper memory, one that recalls what the state once was, and what, under the right form and will, it may yet become again.

It is toward that form, once forgotten and now imperative as the West teeters on the brink of civilizational collapse, and away from the slow unraveling now celebrated as progress, that we now turn.

The modern mind recoils at the suggestion that a small, militarized monarchy might offer serious lessons for statecraft, but it is often at the margins of history, where resources are scarce and survival is not guaranteed, that the essence of political clarity emerges. Prussia, before its rise to continental prominence, was not a land blessed with natural abundance, geographic coherence, or imperial legacy; it was a patchwork realm defined more by vulnerability than strength, yet through the imposition of internal order and the centralization of political will, it elevated itself from near obscurity to a dominant force in Central Europe for over a century.

Its origins were anything but inevitable. Brandenburg-Prussia was not born from the soil like ancient kingdoms, but stitched together through dynastic accumulation, dispersed across fragmented territories that lacked cultural unity and strategic depth. In the wake of the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648)—a catastrophe that decimated the German population and shattered the credibility of the Holy Roman Empire—what remained was not opportunity, but ruin, and the burden of restoration fell not upon theorists or ideologues, but upon rulers who could impose coherence upon the remnants of a devastated political order. In Prussia, that responsibility was assumed with unsparing rigor.

By the time Frederick II ascended the throne in 1740, the groundwork for transformation had already been laid by his father, Frederick William I (reigned 1713–1740), whose reign was defined by a severe economy of means and a relentless focus on institutional consolidation. Known as the “Soldier King,” he curtailed courtly extravagance, filled the granaries, streamlined tax collection, and built a military establishment not for expansionist fantasy but as a bulwark against annihilation. His vision was not guided by ideology or sentiment, but by the cold arithmetic of survival, which treated war-readiness not as adventure, but as the minimum requirement for dignity in a continent ruled by empires.

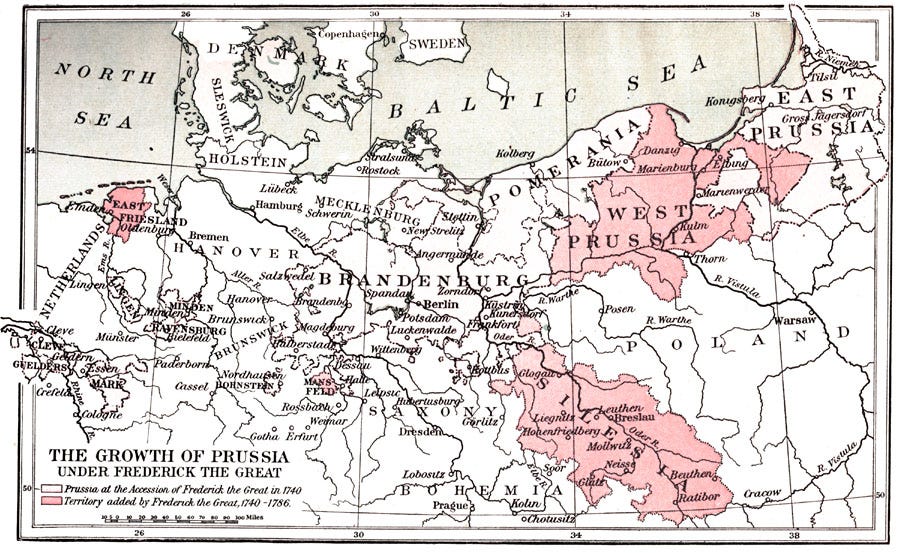

Frederick the Great inherited this hardened machinery, and through it, transformed Prussia from a precarious principality into a disciplined power capable of outmaneuvering and outlasting more populous and resource-rich states. His reign was not defined merely by his military victories, though the seizure of Silesia (1740–1742) and Prussia’s improbable survival in the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) remain among the most brilliant maneuvers of modern European history; what distinguished Frederick was not battlefield genius alone, but the deliberate integration of military, financial, legal, and moral structures into a unified conception of the state that could withstand both foreign assault and internal erosion.

He did not confuse prosperity with indulgence, nor power with visibility, and while he centralized authority, he did not do so for its own sake, but to ensure that no part of the political organism acted against the whole. Every institution in Prussia, from its disciplined army to its austere treasury and rationalized court system, was made to operate in concert with the singular aim of state preservation, and that aim was neither accidental nor diffuse—it emerged from the sovereign’s own philosophy, which held that a state’s greatness lay not in its promises but in its ability to impose form upon itself and endure through time.

Frederick ruled not as a detached monarch, but as a conscious shaper of the organism he had inherited, one who believed that duty superseded comfort, that clarity of law was preferable to proliferation, and that sovereignty must be exercised with vigilance over every aspect of governance. He read widely, corresponded with the philosophes, and cultivated the image of a philosopher-king, but his thought was never an ornament; his writings on law, administration, and economics reflected the hard realities of a fragile polity surrounded by hostile neighbors, and his reforms were never designed to please the intellectual class, but to secure the bones of the state beneath it.

Under his rule, Prussia came to possess not only an army of unmatched discipline and a bureaucracy of remarkable efficiency, but a legal framework that sought to restrain corruption, ensure continuity, and align civil law with the moral purpose of the regime. He abolished torture in criminal procedure, streamlined the appeals process, and resisted both the stagnation of archaic precedent and the chaos of excessive innovation. His court did not overflow with flatterers or speculators, and his own life was marked by austerity, self-restraint, and personal involvement in the operations of the state, not for show, but because he believed the ruler must govern not merely in law, but in example.

That he accomplished this while ruling over a population barely exceeding five million, with a scattered and insecure territorial base, only magnifies the achievement. Prussia lacked the deep cultural unity of France, the naval protection of Britain, and the raw demographic scale of Russia or Austria; yet it endured, not because it assimilated into the incoherence of greater powers, but because it concentrated its energies into survival, refinement, and purpose. Its language, its traditions, and even its elite were divided, but through the imposition of will, those divisions were subordinated to something higher.

Prussia under Frederick did not promise equality, nor universal participation, nor liberal self-expression. What it offered instead was continuity, order, and a sense of direction, a state that knew what it was and refused to lie about it. It demanded much of its citizens not because it viewed them as expendable, but because it understood them as integral to a project that would outlast them. Its legitimacy was not manufactured through slogans, nor purchased through redistribution; it was earned through the visible discipline of its institutions and the visible integrity of its leadership.

In an age such as ours, where language has become a refuge for cowardice and the state is little more than a clearinghouse for temporary demands, the memory of such a form appears almost unreal. But it is not beyond recovery. The same pressures that once forged Prussia—scarcity, insecurity, geopolitical fracture—are returning to the West, and those who imagine that modern institutions can continue drifting forward indefinitely, powered by inertia and sentiment, are blind to the consequences of fragmentation without form.

The future will not be built by democratic majorities. It will not be administered into existence. It will be shaped deliberately, by those willing to think as sovereigns, to act as stewards, and to reclaim the principle that the state is not a marketplace of opinions, but a moral organism whose highest function is to endure.

That principle, so long forgotten in the West, was not only once known—it was once embodied. In a kingdom lacking in natural resources, surrounded by enemies, and fractured by history, the moral organism of the state was not treated as metaphor but as command. Prussia, under the rule of Frederick the Great, did not possess the advantages of scale, wealth, or geographic insulation. What it possessed instead was coherence. Its survival was not assured by ideology or by consensus, but by the deliberate subordination of all functions to a singular directive will, one that did not apologize for hierarchy, did not mistake process for legitimacy, and did not permit the machinery of government to operate in contradiction with the aims of the whole.

Unlike the modern state, which splinters its authority across overlapping ministries, regulatory agencies, outsourced contracts, and multinational obligations that multiply complexity while disavowing responsibility, Frederick’s Prussia was ordered from the center outward, with its military, courts, treasury, and foreign policy functioning not as autonomous sectors but as instruments of one political organism, unified in purpose, harmonized by command, and disciplined by the sovereign presence of a ruler who did not govern by proxy.

The army, the courts, the fiscal administration, and the diplomatic corps did not operate as rival bureaucracies or siloed departments; they were integrated extensions of a single mind that regarded governance not as the arbitration of competing interests, but as the imposition of coherent direction upon a fragile and often hostile world. War was not waged to satisfy public opinion or to secure moral prestige, but to defend and consolidate the state’s existence; law was not conceived as a forum for litigious innovation or social engineering, but as a moral framework to restrain corruption and preserve civil peace; finance was not a mechanism for short-term redistribution or political bribery, but a reserve of strength to be conserved and deployed with purpose in moments of national crisis.

What gave this structure its internal unity was not uniformity or administrative cleverness, but hierarchy—an understanding that sovereignty, if it is to be real, must be singular. It can be delegated in its operation, but not in its essence. Once authority is fragmented, it ceases to direct; it reacts, it manages, it negotiates itself into paralysis. Frederick’s state did not function on the illusion of shared sovereignty. It was governed by a principle that placed the whole above the parts, that judged policy by its fitness to the regime’s long-term continuity, and that located responsibility not in process, but in the character of the sovereign himself.

That sovereignty was not ornamental. It was not legalistic or ceremonial. It was active, vigilant, and personal. Frederick did not govern through spectacle, nor did he outsource the burdens of rule to technocrats or consultants. He studied the movements of armies, intervened in questions of legal procedure, and monitored the disposition of funds not because he distrusted his administrators, but because he understood that a state divided in attention becomes divided in soul. His interest was not control for its own sake, but order in the service of survival.

He personally reformed military doctrine, oversaw the training and readiness of his regiments, and refused to allow aristocratic privilege to override competence in the officer corps. He banned courtroom rhetoric as a means of manipulation, insisting that justice depended not on eloquence but on clarity. He codified laws, shortened legal appeals, and abolished torture not in the name of ideological progress, but to restore confidence in the integrity of public judgment. When he stated that it was better to spare twenty guilty than to punish one innocent, he was not indulging sentimentality, but reaffirming the moral restraint without which the law becomes indistinguishable from tyranny.

What he achieved was not balance in the modern sense of compromise, but integration. The state functioned not as a collection of competing ministries but as an organism, vulnerable but whole, in which each part—military, legal, administrative, and diplomatic—was shaped and directed according to its contribution to the survival of the entire body. He did not expand state power to micromanage daily life, but disciplined it so that the fundamentals of life, including security, law, duty, and continuity, could persist without collapse.

This structure was not the product of abstract theory or speculative design. It was forged under pressure, tested repeatedly by war and geopolitical isolation, and refined by necessity. Prussia did not benefit from the buffers of geography or the inheritance of empire. Its strength came from the concentration of its will, from the subordination of its functions to direction, and from the sovereign’s refusal to allow the state to drift into contradiction or dissolution. Its unity was not maintained through propaganda or surveillance, but through form.

The modern state cannot grasp this because it no longer believes that coherence must be imposed. It imagines that balance will emerge from diversity, that justice will emerge from process, and that leadership can be safely replaced by administration. But no organism survives on metabolism alone. The state is not kept alive by the movement of parts, but by the presence of a head. Prussia endured because it refused to abdicate this fact. Where the modern West multiplies laws to disguise its loss of direction, Prussia concentrated authority to preserve its direction. Where the modern West confuses activity with governance, Prussia disciplined its activity in service of governance. Where the modern West dissolves responsibility into bureaucracy, Prussia reasserted it at the summit.

None of this implies that Frederick’s regime can or should be copied. Like all regimes, its structure was a unique product of it time. Its conditions cannot be replicated. But the principle that animated it is eternal: the state cannot survive as a collection of detached functions. It cannot be managed into meaning. It must be governed. And governance requires sovereignty—not just in name, but in form, in presence, and in will.

None of this implies that Frederick’s regime can or should be copied. Like all regimes, its structure was a unique product of its time, forged in the crucible of conditions we cannot replicate. But the principle that animated it is eternal: the state cannot survive as a collection of detached functions, it cannot be managed into meaning, and it cannot be made whole by appealing to consensus or outsourcing judgment to process. It must be governed. And governance requires sovereignty not only in name but in form, in presence, and in will.

That understanding, dismissed today as archaic or authoritarian, was once foundational. There was a time when it was not controversial to say that a state existed for something beyond the fulfillment of individual appetites or the preservation of abstract rights. There was a time when form mattered, when hierarchy was understood not as oppression but as structure, and when sovereignty was not a specter to be feared, but a necessity to be fulfilled. That time has passed, and the moral vocabulary it relied upon has been largely erased, yet the reality it described has not vanished with it. A state still either coheres or collapses. It either endures or dissolves. It either rules or is ruled by others.

The lesson is not that we must reconstruct Prussia, nor that the future lies in the imitation of a vanished monarchy whose rituals and institutions were bound to a cultural ecology that no longer exists. That world was rooted in soil we no longer till, shaped by dangers we no longer recognize, and inhabited by men whose formation depended on suffering and struggle we have largely forgotten. Its dynasties were legitimized by religious order, its hierarchy sustained by martial ethic, and its cohesion made possible by a shared sense of transcendence that has been replaced in our age by consumer preference and managerial inertia. All of that is gone, but what remains is not nothing. What remains is the principle, namely that political form is not accidental, that sovereignty must reside somewhere, and that the state, if it is to endure, must be organized around a purpose higher than administration.

This was once understood across civilizations and epochs. The ancients knew it when they conceived of politics not as market or contract, but as the soul of the city made manifest. The medieval world institutionalized it in the fusion of throne and altar, where kings did not merely rule but were anointed to do so. Machiavelli understood that a republic without virtue would fall to corruption, just as Bodin warned that sovereignty divided is sovereignty undone. Even the modern philosophers most celebrated by liberal democracies—Hobbes, Rousseau, Hegel—never believed the state was neutral. They saw it as the instrument of civil unity, the mechanism by which man rises above appetite and chaos to inhabit an ordered world. What united all these traditions was not a shared constitutional model, but the recognition that the form of rule shapes the destiny of a people, and that no amount of rights or regulations can compensate for the absence of a coherent and enduring political architecture.

Liberalism, in its modern expression, has severed itself from that inheritance. It treats the state not as a moral form, but as a facilitator of preference. Its only ethic is consent, its only telos comfort. It fears the assertion of power while multiplying the need for enforcement, denounces hierarchy while erecting new layers of unaccountable authority, and sanctifies inclusion while systematizing exclusion against anything that threatens its fragile legitimacy. It does not command, it coordinates. It does not govern, it manages. It does not inspire, it audits.

And yet even in its decline, it still depends on the residues of older forms. The liberal state assumes shared memory while dismantling the institutions that once produced it. It assumes a coherent population while importing new ones it cannot assimilate. It assumes mutual obligation while severing the moral and ethnic ties that once bound citizen to state. As these assumptions erode, the system cannot respond with clarity or strength. It can only repeat itself, promising safety while unleashing disorder, invoking rights while denying identity, expanding surveillance to mask its loss of legitimacy.

This trajectory does not end in renewal. It ends in rupture. A regime that cannot define the people in whose name it governs, that criminalizes loyalty while subsidizing rootlessness, that teaches its children to despise their ancestors while placing their future in the hands of foreign masses, cannot endure. Whether the crisis arrives through war, demographic inversion, economic breakdown, or internal collapse, the result will not be a more refined form of liberalism. It will be the return of something older, something harder, something real. The age of process will give way once more to the age of form.

This will not mean a regression into monarchic nostalgia or fascistic theatrics. It will mean the emergence of a new elite, not in the sense of wealth or visibility, but in the classical sense of those who are willing to assume responsibility, to think historically, to act hierarchically, and to govern not for applause but for posterity. They will not require old titles or bloodlines. They will need to embody authority, to make judgments without apology, and to impose limits not because it is easy but because it is necessary.

Their legitimacy will not come from slogans or ballots or constitutions. It will come from what they do. From the continuity they restore, from the dignity they uphold, from the children they defend, and from the future they carve out of ruins. They will not ask for permission. They will act. And in acting, they will remind the world that the purpose of the state is not to reflect society, but to shape it.

For the managers of the current order, this is unthinkable. They cannot imagine a polity that speaks with one voice, a people that demands more than comfort, or a future shaped by will rather than inertia. But their imagination is not required. History is moving with or without them. The tectonics of the world shift. Asia asserts itself. Africa expands. Traditions once thought extinct begin to awaken. The liberal imperium that conquered the twentieth century now lurches toward dissolution not because it was violently overthrown, but because it consumed itself.

What comes next will not be born from its promises. It will rise from the truths it denied.

And the only question that remains is who will be ready when it does.

Teilhard’s vision of evolution’s God seems like the best “purpose higher than administration” available to the West at this time