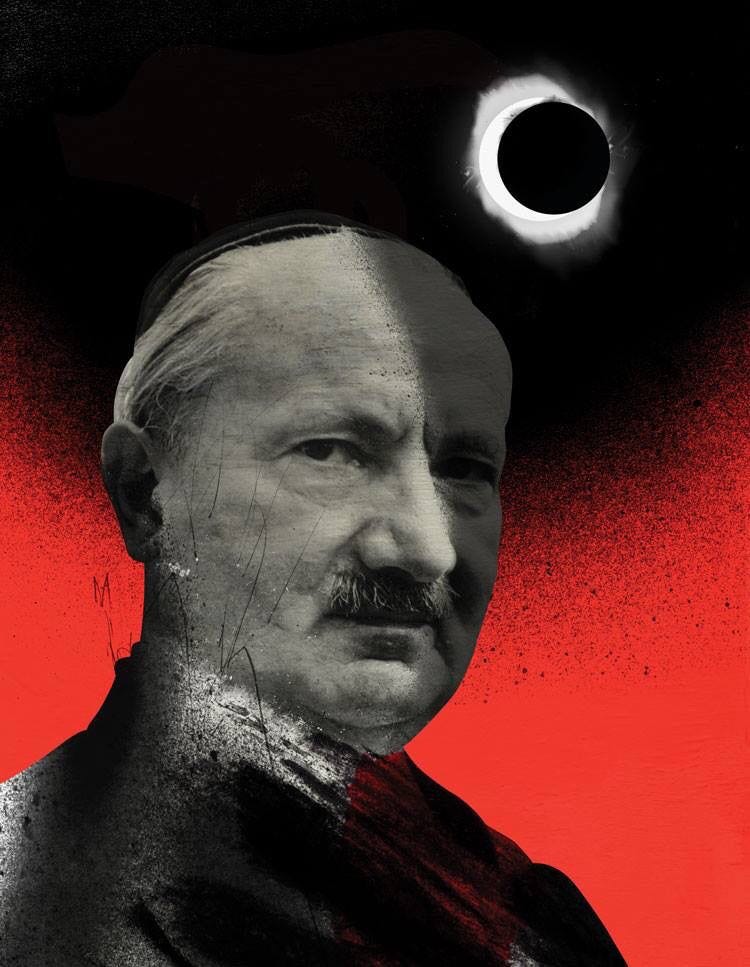

Heidegger and the Question of Being

An inquiry into metaphysics and the loss of meaning in the modern world

To think metaphysically is to face the most ancient and inexhaustible question of the West: what does it mean to be? From that question philosophy was born. In asking what is real, man confronts not only the world around him but the hidden ground upon which both he and the world depend. Metaphysics was once the highest labor of the Western mind, the effort to penetrate appearance and reach the foundation of existence itself. Few inquiries have gone so far, and none is so neglected today.

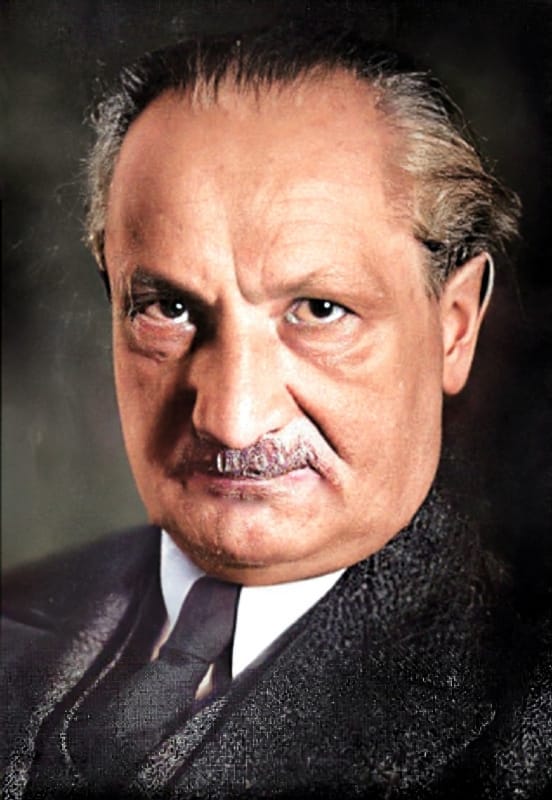

This reflection turns to the thought of Martin Heidegger, for whom metaphysics was not a theory but a task. He treated it as the unfolding destiny of Western thought, a history that began in the wonder of the Greeks, passed through the theological imagination of the Christian world, and culminated in the technological age. What began as an openness to Being ended in a world governed by method and control. The history of metaphysics is the story of this forgetting.

The first Greek thinkers sought the principle from which all things arise. They called this phusis. The word means both “to grow” and “to arise,” and it expressed the movement through which beings emerge into presence. For them, the world was alive in its becoming; phusis named that self-showing through which existence discloses itself. The world was a field of revelation, not a store of objects to be measured or possessed.

In the thought of Heraclitus, phusis was the ever-living fire, a process of transformation in which all things are born, perish, and are reborn. “The thunderbolt steers all things,” he wrote, meaning that the hidden law of the cosmos reveals itself through ceaseless conflict. Order was not imposed from outside but arose within the strife of opposites. Parmenides, by contrast, denied that change was ultimately real. For him, only Being is, and non-being is not. The senses deceive, but reason perceives the eternal presence that neither comes to be nor passes away. Between these poles of flux and permanence, the entire drama of Greek philosophy unfolded.

When the Romans rendered phusis as natura, a subtle transformation occurred. Natura means “birth” or “what is born,” but in time it came to signify the totality of created things. The living event of emergence became the inventory of what exists. Reality was no longer understood as a process of self-revealing but as an order of finished entities. From natura the modern word “nature” derives, and with it the sense of the world as something to be observed, classified, and eventually mastered. What had once shown itself withdrew, and what remained was the surface of things. The first seeds of what Heidegger would later call Gestell, or enframing, were already present in this shift: the tendency to view the world as a collection of objects available for use rather than a mystery that reveals itself.

Plato sought permanence within the flux of things. He conceived the eide, the Forms, as perfect patterns underlying appearance. For him, the sensible world was a realm of becoming, always changing and never truly real. Only the eide, eternal and unchanging, possessed true Being. Knowledge, therefore, was recollection, a turning of the soul away from the shadows of perception toward the light of what is always the same. In this turning, Being was lifted out of the visible and placed within a higher order of pure intelligibility. The visible world was no longer revelation but imitation, an imperfect copy of what exists beyond it. Plato thus divided reality into two regions: the eternal and the temporal, the world of truth and the world of opinion.

Aristotle inherited this division but sought to reunite the two realms. He brought the Forms back into the world by locating them within things as their inner essence. Every being, he taught, is composed of matter and form, potentiality and actuality. Movement and change are the striving of potentiality toward fulfillment in actuality. At the summit of this order he placed the unmoved mover, pure actuality, which causes motion not by force but by attraction, as the object of love and longing. All things, by their very nature, seek to participate in this perfection.

With these doctrines, the path of Western metaphysics was set. Being came to be understood as presence, as that which endures and stands firm. The divine became the highest instance of this presence, the perfect actuality upon which all imperfect beings depend. Here, Heidegger observed, lies the origin of what he called ontotheology: the fusion of ontology and theology, in which the question of Being is replaced by the search for a supreme being. Once Being is interpreted as the highest entity, its mystery is lost. What was once the ground of appearance becomes another thing that appears. The essence of Being, its giving, its withdrawal, its self-concealment, falls into obscurity.

This new orientation prepared the way for the later synthesis of Greek philosophy and Christian revelation. When the early theologians adopted the conceptual tools of Plato and Aristotle, they preserved the same metaphysical architecture. God became the unmoved mover and the supreme idea, the pure actuality from which creation proceeds. The world ceased to be a self-unfolding order and became an artifact of divine will. Thus the ontotheological structure endured, now sanctified by faith. The transcendent replaced the immanent; the sacred withdrew from the earth into heaven. The living mystery of Being was translated into the language of creation and command.

Heidegger saw in this change the origin of the West’s forgetfulness of Being. Metaphysics, as it developed from Plato onward, became a long attempt to secure reality by identifying it with something stable: matter, form, spirit, God, or mind. Each epoch selected a principle, raised it above the rest, and treated it as the ultimate ground. In each, a being was mistaken for Being itself. This is the ontological difference: the separation between what is and the act of being. It is the foundation of all Western philosophy and the root of its decline.

To recognize that difference is to see that Being is not one among the things that are. It is not contained within the world but grants the world its space of appearance. It is the clearing in which every presence can emerge. Philosophy cannot define it, for Being is what allows definition to occur. To think metaphysically in the Heideggerian sense is not to construct a system but to dwell in the openness through which reality discloses itself.

Being is near, yet it escapes possession. It gives itself partially, concealing itself as it reveals. Each attempt to fix it leads to a deeper obscurity. The history of metaphysics is thus a history of forgetfulness, the gradual substitution of representation for revelation. What began as wonder hardened into method; what was once revelation became calculation.

The Greeks still carried within them the sense of the sacredness of phusis. It was not creation, for creation presupposes a craftsman distinct from the world. Phusis was self-arising, the spontaneous motion through which things came into presence. Even the gods were borne by its order, not standing above it but shining within it. To live in harmony with phusis was to dwell in the rhythm of Being, to see that all that exists—mountain, storm, star, and man—moves within one continuous cycle of arising and return.

Greek tragedy preserved this understanding. In Aeschylus and Sophocles, fate was not arbitrary decree but the structure of Being itself. The downfall of the hero disclosed the limits of man’s pride before the eternal order. Art, worship, and thought were joined in a single act of remembrance. The Greeks still dwelt in the truth of Being without seeking to dominate it.

Over time, that openness closed. The logos, once meaning to gather and let appear, hardened into logic and technique. The poetic language of revelation was replaced by the technical language of system. The philosopher displaced the poet, and thought was turned into explanation. The measure of truth became exactness rather than depth.

This movement, from phusis to natura, from aletheia to correctness, from Being to ontotheology, was what Heidegger sought to uncover. His purpose was not to revive Greek religion but to recover the disposition that had once made philosophy possible. To think Being anew is to recover astonishment, what the Greeks called thaumazein, the wonder that there is something rather than nothing.

Modern man no longer feels this wonder. He regards the question of Being as meaningless, for he measures all things by their use. Yet this blindness is not an accident; it is the end of the same path that began in Greece. The will to master and to define has reached its perfection in the technical world, where all things are transparent and nothing is revealed. The machinery of knowledge has become the machinery of concealment.

To recover the question of Being is not to return to abstraction but to recover awe. Truth is not possession but participation. Knowledge begins in reverence. The thinker’s task is to let Being speak rather than to speak over it. The path of metaphysics, rightly understood, is not the pursuit of mastery but the discipline of listening.

That discipline was not maintained. The world, once luminous in its own revealing, came to be regarded as a creation distinct from its source. The sacred was withdrawn from the earth and placed above it. What the Greeks had experienced as an unfolding became an act of will. The structure of thought endured, yet its spirit changed, and from that change the Christian world arose.

In the Christian age, Being was no longer the immanent rhythm of life but the decree of a transcendent mind. The cosmos, once experienced as self-showing, was now understood through the relation of maker and made. Augustine turned inward, seeking in the soul what the ancients had found in the openness of the world. In that inward light, Being became inseparable from divine presence, known through illumination rather than disclosure. Truth was no longer unveiled but revealed.

Aquinas later sought reconciliation between this theology and Aristotle’s metaphysics. By identifying God with ipsum esse subsistens, the pure act of being itself, he preserved Aristotle’s realism while grounding it in the Creator. Existence became not the shared field of beings but the radiance of a single source. Participation was replaced by dependence, order by hierarchy, and metaphysics became theology in another form.

For the medieval thinker, this transformation was not a loss but a fulfillment: the world’s intelligibility confirmed its divine origin. Yet for later philosophy, it marked the beginning of estrangement. The sacred was preserved but rendered distant; the wonder that once dwelt in things themselves was confined to the mind that contemplated them. To know truth became to submit intellect to revelation, and the freedom of thought was exchanged for the security of faith.

From this transformation emerged the medieval order, vast and architectural, in which every creature held its appointed place. Reality was conceived as a hierarchy descending from the divine intellect through the angelic choirs to the material world. Each degree of being participated in the perfection of the One above it, forming a chain of causality that bound heaven and earth in a single order. God stood as architect, the world as His design, man as interpreter. Within this vision, the cosmos was intelligible because it was created in wisdom; its beauty reflected the clarity of divine reason. Yet the same order that gave grandeur and stability imposed distance. The world, once luminous with its own necessity, now shone only by borrowed light. The immediacy of presence yielded to mediation, and Being itself was understood through will. Truth no longer revealed itself in things but in obedience to the command that instituted them.

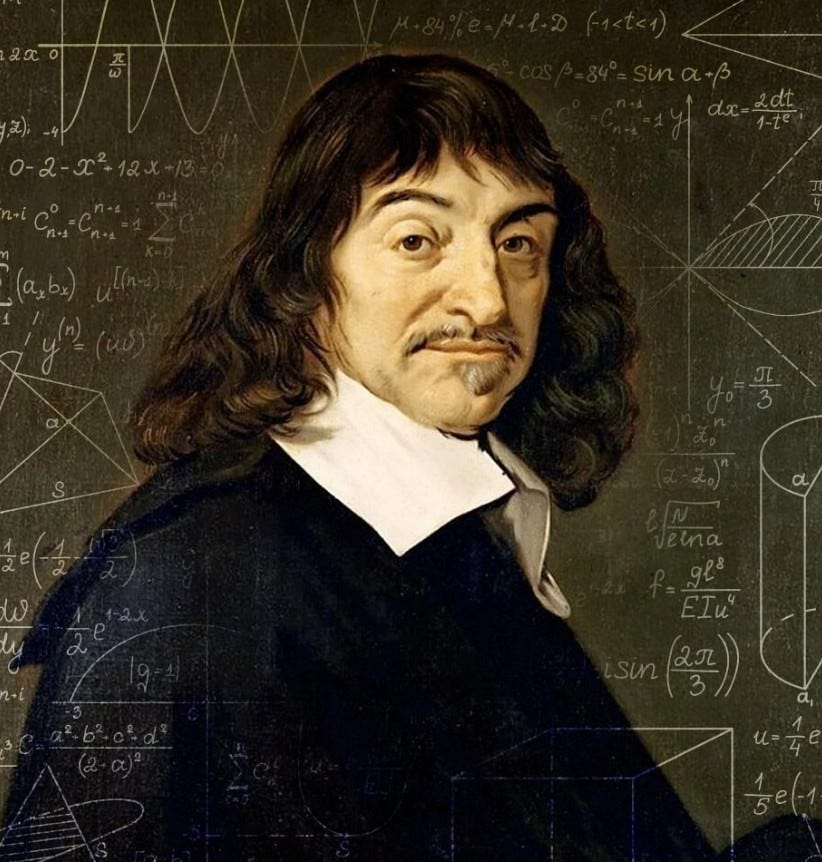

When modern philosophy arose, it did not abolish this architecture but merely reversed its direction. The transcendent will of God was replaced by the self-certainty of man. Descartes sought an unshakable ground of knowledge, finding it not in creation but in the act of thinking itself. The cogito became the new first principle, and Being was reduced to what could be represented by consciousness. The object no longer disclosed itself; it was constructed by the clarity of the subject. Husserl carried this transformation to its extreme. The world became the intentional horizon of consciousness, dependent upon acts of meaning that gave it form. What the Greeks had called the clearing of Being was now the field of subjectivity. Kant then completed this inward turn by limiting knowledge to phenomena shaped by the categories of human reason. Reality became appearance within the bounds of cognition, and truth the coherence of representation.

Thus modernity did not escape metaphysics but enthroned man as its center. The divine artificer became the scientist, and the world was rendered as mechanism. The question of Being gave way to the question of method. Truth no longer meant revelation but verification. Knowledge was measured by certainty, not by depth, and the highest aim of thought became control.

In Hegel this rationalization reached its grand synthesis. Spirit, once the breath of existence, became the movement of reason realizing itself through history. The world was no longer revelation but reflection, the mirror in which mind beheld its own unfolding. History itself became logic in motion, a vast dialectic in which every contradiction found reconciliation in higher unity. The Absolute was no longer transcendent but immanent within the process of thought. Reality became the self-knowledge of reason, and the mystery of Being was absorbed into comprehension. The living movement of existence was transfigured into the system, vast and complete, in which nothing could remain unaccounted for. What had once stood in awe before Being now sought to encompass it within the Concept. In this total understanding the modern spirit reached both its zenith and its exhaustion, for when everything is explained, nothing is left to wonder at.

Heidegger discerned in this consummation the hidden poverty of the Western soul. The triumph of reason concealed the loss of dwelling within what is. The world stood illuminated but hollow, exposed yet without presence. The light of understanding became the glare of control, and knowledge, having conquered mystery, found itself without meaning.

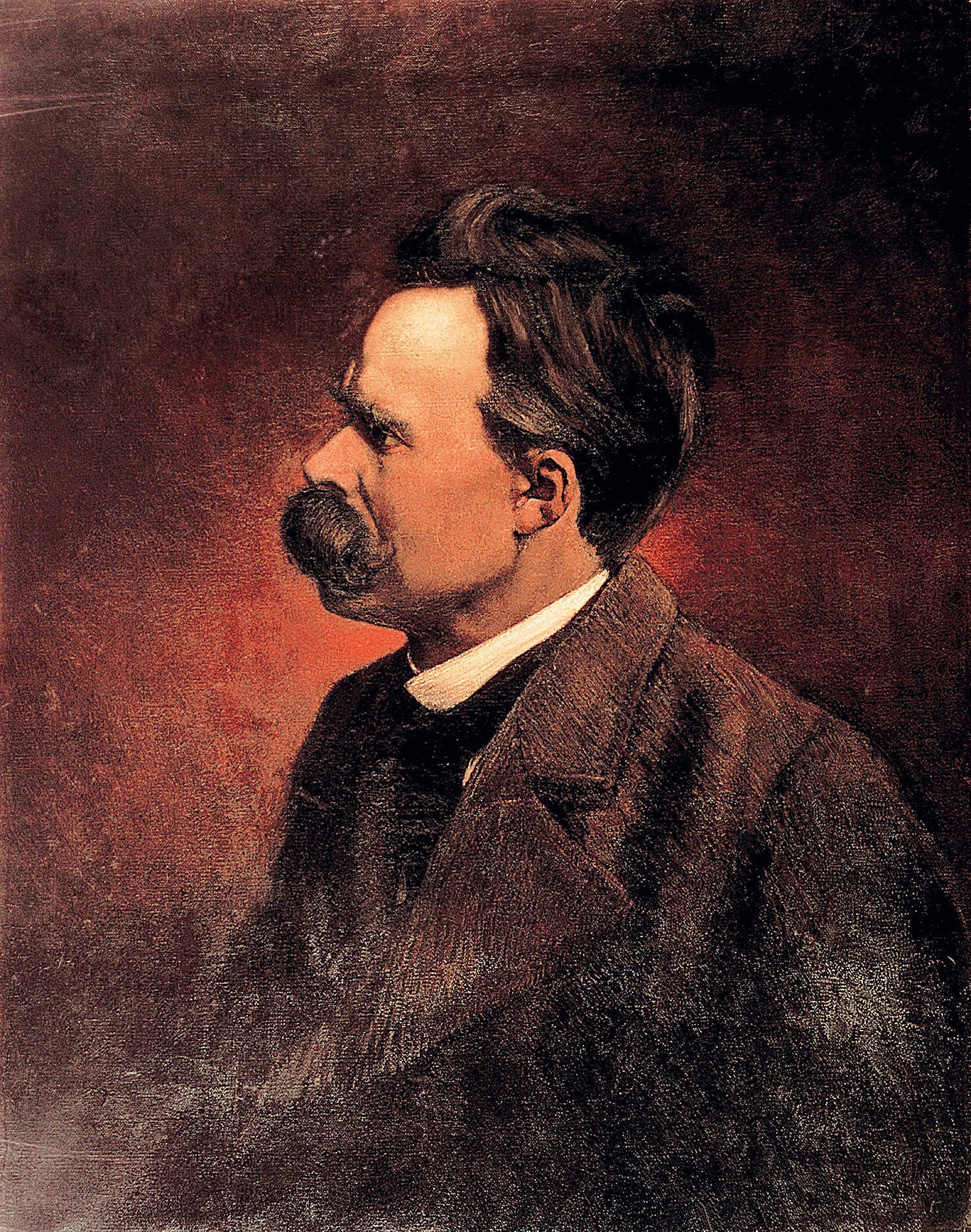

Here Nietzsche appeared as both heir and prophet. He perceived that behind the metaphysics of reason lay the will to power, the primordial impulse to shape and to command. Beneath every claim to truth he saw a deeper striving, the assertion of life against chaos. What the philosophers had called objectivity was itself an act of valuation, a will that imposed order upon becoming. He proclaimed the death of God not as an event of disbelief but as the culmination of metaphysics: the exhaustion of all transcendent measures. With the collapse of the highest value, man became measure unto himself. Yet this freedom revealed a new bondage, for the will that once sought to know the world now sought to master it. In Nietzsche’s vision, the technological age already stirred, the reduction of Being to energy, of truth to function, of man to the last, contented creature, satisfied yet emptied of soul. His insight exposed the destiny of modernity: that the conquest of nature would end in the conquest of man himself.

Technology was not a mere collection of tools but a revelation of Being’s final forgetting. In the mode of Gestell, all things stand forth only as resources. Nature becomes raw material, and even man becomes stock. The earth, once the living ground of emergence, is reduced to standing-reserve, awaiting command. The world appears transparent yet hollow, illuminated only by the light of utility. The will to mastery that Nietzsche foresaw thus becomes the metaphysical destiny of the age. The danger lies not in machines but in the spirit that animates them: the belief that nothing has value except as use. What was once the revelation of Being now becomes its concealment, for when everything is available, nothing is near.

Yet concealment is never absolute. Even in this destitution, something of Being’s light endures. Man remains the being who can feel its absence and thus be called to remembrance. In the moment of greatest impoverishment, the possibility of renewal begins. Heidegger named this moment Ereignis, the event of appropriation, wherein Being and man encounter one another anew. It is not discovery but belonging, the return of intimacy between the mortal and the mystery that grants him place. To recognize Ereignis is to see that man does not possess Being but is possessed by it. In this event, knowledge becomes gratitude and thought becomes care. The call of Being demands not mastery but guardianship, a readiness to let what is appear in its own time.

To prepare for such an encounter demands a new discipline of thinking. Philosophy must turn from assertion to listening, from construction to waiting. Heidegger called this der Schritt zurück, the step back from will to wonder. To dwell, in his sense, is to inhabit the openness of the world, to recognize the belonging together of earth and sky, mortal and divine. Man is not sovereign but guardian of the clearing in which beings appear. The house of Being is language, and man, as Dasein, is its custodian. The German poet Hölderlin intuited this truth in the darkening age, writing that “poetically man dwells upon this earth.” Poetry stands nearer to truth than science, for poetry listens where science commands.

The recovery of Being depends not on progress but on remembrance. It requires that man accept his finitude, renounce domination, and recover awe. This remembrance is not nostalgia for what has passed but a return to origin, to the archē, the beginning and abiding principle of all things. In remembering Being, man remembers measure. He sees again that existence is gift, not possession, and that knowledge must begin in reverence. To think in this way is not to regress but to awaken, for in gratitude thought becomes again what it was at its birth: the vigilant care of what is.

Through remembrance man recalls himself. He learns that his essence is openness, not control. He is not the master of what is but the clearing in which it shines. Forgetting this, he falls into the destitution Heidegger called the fall of Dasein, the condition of treating the world as object and himself as its measure. In truth, man’s being is Sorge, care, the guardianship of what is. Through care he preserves the world rather than consumes it.

The forgetting of Being is therefore not only an intellectual failure but a moral impoverishment. It is the loss of gratitude, the dimming of reverence for existence itself. Nihilism is not the absence of belief but the reign of utility, the loss of measure. It is the epoch of the last man, clever, comfortable, and incapable of awe. Against this condition Heidegger calls for the reawakening of thaumazein, the astonishment from which philosophy first arose and by which the West may yet be renewed.

The fate of the West depends upon this renewal. For all its triumphs, the technological age has left man inwardly impoverished. Surrounded by abundance, he lives without center. The recovery of Being is therefore the recovery of form, the restoration of limit, the rediscovery of dwelling. It is not a return to myth but a new beginning in thought, where philosophy and poetry again serve truth. In this return, the first words of Parmenides echo once more: “For the same is thinking and being.” The path of thought closes where it began, in the stillness before the mystery of presence.

To think metaphysics anew is to move beyond the systems that have enclosed it. Every doctrine, once codified, turns against its origin and forgets the ground that gave it life. Heidegger’s final teaching points toward silence, not as resignation but as mastery, the silence of one who commands himself. Philosophy fulfills itself not in endless discourse but in stillness, where thought becomes vigilance.

What Heidegger sought was not a rigid system of ideas but a steadfastness of soul before Being, the courage to face what reveals itself without concealment or control. When man regains this strength, he stands again within the clearing of truth, where the world discloses itself not as an object to be used but as a trust to be preserved. Knowledge becomes discipline, and thought finds its fulfillment in the quiet guardianship of the light that endures

Primordial phusismaxxing is back on the menu boys.

"Concepts create idols,only wonder comprehends"

St. Gregory of Nyssa