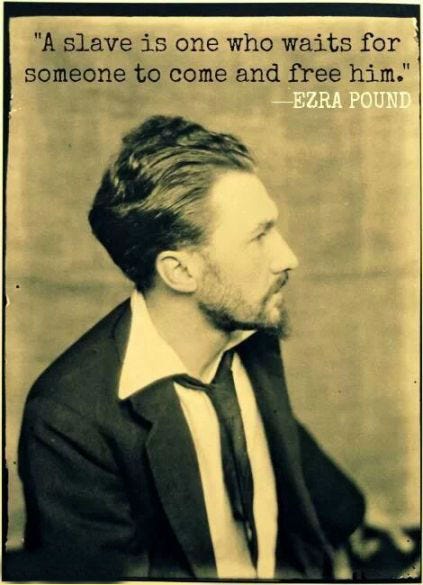

Ezra Loomis Pound (1885–1972) was not merely a poet, but a civilizational force, a lightning bolt hurled into the cultural and political tempests of the twentieth century. Though his name is most often linked to the revolution in modernist verse, to see Pound solely as a literary innovator is to misunderstand the scale of his ambition. He was a critic of decadence, a translator of lost worlds, an economic theorist, a political visionary, and a guardian of form in an age increasingly estranged from beauty, order, and truth.

Many approach Pound with caution, and not without reason. His style is dense with allusion, studded with foreign tongues, and marked by sudden leaps across epochs and traditions. Yet the difficulty is not a matter of obscurity for its own sake. It reflects a deeper conviction: that culture is a thread of memory, that the poet must serve as its vessel, and that civilization rests upon a foundation of moral and aesthetic order. To read Pound is to step into the long corridor of Western civilizational memory, guided by a man who refused to dim the light for the comfort of his fellow travelers.

For those beginning a serious engagement with Pound, it is best to start with his prose rather than his poetry. Impact: Essays on Ignorance and the Decline of American Civilization gathers his reflections on culture, politics, and the spiritual malaise of the twentieth century. It is an ideal introduction to his worldview. A broader survey can be found in Selected Prose: 1909–1965, edited by William Cookson, which includes Pound’s writings on literature, history, language, and the obligations of the artist.

One of the most essential texts in Pound’s corpus is Guide to Kulchur, a fierce and wide-ranging inquiry into the decline of culture and the collapse of philosophical seriousness. Beginning with Confucius and proceeding through the cardinal figures of the Western tradition, Pound traces the erosion of meaning to its source in the degradation of language. His fundamental conviction is that truth begins with correct naming, that words must reflect the true nature of things and not obscure or distort them, and that the rot of civilization begins when language loses this correspondence to reality. The style is elliptical and urgent, but the insights it yields are enduring and at times prophetic.

To understand Pound’s political thought, one must turn to Jefferson and/or Mussolini, where he draws a deliberate and unapologetic comparison between the founding principles of the American Republic and the hierarchical order of Fascist Italy. He believed that both systems, in their original conception, offered meaningful resistance to the encroaching rule of international finance and the erosion of ethnocultural sovereignty. His wartime broadcasts, collected in Ezra Pound Speaking: Radio Speeches of World War II, reveal a man for whom economics and morality were indivisible. Usury, in his eyes, was not merely a financial crime but a metaphysical perversion—a force that commodifies life, debases beauty, and corrupts the soul of European man. These texts are demanding and incendiary, but essential for understanding Pound’s vision of history as a battlefield between order and dissolution.

When one is prepared to enter Pound’s poetic world, the proper beginning is Ezra Pound: Poems and Translations. This volume offers not merely a selection, but a foundation: it presents the full range of his verse, from the crystalline beauty of his early lyrics to his rigorous translations from Latin, Provençal, and Chinese, and the daring formal experiments of his middle years. These poems do not merely adorn a tradition—they wrestle with it, reanimate it, and carry it forward. They reveal a sensibility shaped by the past yet restless for renewal, a craftsman who treated language not as ornament, but as the medium through which thought becomes form. It is here, in these measured lines and metrical subtleties, that Pound’s lifelong struggle for cultural clarity first takes shape. Omitted from this collection, however, is The Cantos—a work that stands apart in both scale and ambition.

The Cantos is Pound’s most famous work, and his unfinished epic, the culmination of his vision as poet, historian, aestheticist, and polemicist. It is a poem of fragments, not the ruins of a failed structure but the scaffolding of an unfinished temple, bearing witness not to collapse but to the magnitude of the ambition behind it. In this work, Pound sought to gather the essential inheritance of the West: its memory, aesthetic forms, and governing ideas, into a single sustained poetic effort. What emerged is not a coherent system unfolding with logical continuity, but a living archive, animated by beauty, marked by warning, and unresolved in its final meaning. The text is dense and demanding, but for the discerning reader, it offers lasting reward and repays careful study with rare insight.

To read Pound is to encounter a man who did not merely write about civilization, but sought to alter its direction. For him, the artist was not a bystander, but a sacred custodian of meaning, bound by duty to preserve what was vital and expose what was false. The poet’s role extended beyond verse into the realm of truth, justice, beauty, and memory. Art, in his vision, was not a luxury or diversion, but a form of responsibility. He believed that the health of a civilization could be discerned in its literature, its coinage, and its clarity of expression, and that the artist, moreover, was central to its preservation His work demands discipline and awareness, but in return it offers a vision of genuine high culture—an alternative to the consumerist spectacle that today passes for art—and reveals culture not as entertainment for the throng, but as destiny for the few.

Well, at least they didn't kill him.

Many insightful "what was really goong on" people didn't make it out of the 40's alive.