There are books whose relevance fades with time, overtaken by fashion or rendered obsolete by changing fears. The Camp of the Saints is not one of them. Written in 1973 by the French novelist and explorer Jean Raspail, it did not merely anticipate the migrant crises of the twenty-first century—it illuminated their moral and psychological foundations in advance, as if guided by a kind of tragic foresight. What Raspail depicted in his dark, satirical novel was not simply an invasion by sea, but a spiritual unravelling: a surrender justified by charity, embellished with guilt, and enforced by the very institutions once entrusted with defending Europe.

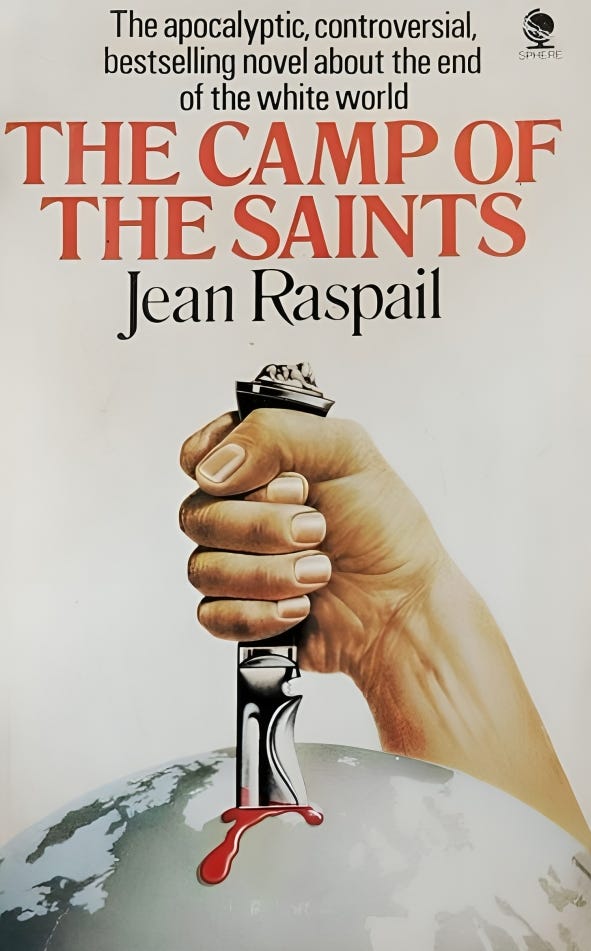

That this novel, long denounced, suppressed, and driven out of print in the English-speaking world, now returns in a new English translation of the final 2011 French edition is no minor event. Vauban Books will release it in the summer of 2025. It marks the reappearance of a prophetic work at the precise moment of its vindication. For what was once dismissed as dystopian exaggeration now resembles factual reporting: NGO vessels transporting migrants across the Mediterranean, swarms of caravans streaming across the mainland, media campaigns portraying mass influx as salvation, political elites unwilling to draw lines or safeguard their nations. The book’s grotesque parade of ideological clowns, spiritual castrati, and self-righteous traitors no longer reads as hyperbole. If anything, the real world has exceeded its warnings.

Raspail was not a provocateur; he was a patriot in the true sense of the word. He did not fantasize about the catastrophe he described; he feared it and hoped to prevent it. But unlike the sterile evasions of official commentary or the lifeless jargon of policy, his fiction dramatized the essential truth—not that immigration policy might fail, but that a people might forget how to live. The French, and by extension the European, were portrayed not as victims of invasion but as authors of their own undoing, having confused pity with virtue and forsaken the instinct to endure.

To read The Camp of the Saints today is not to escape into fantasy; it is to be jolted awake from one. It is to confront the cost of humanitarian piety, racial abasement, and the universalist creed that has hollowed out the West. This essay is not merely an interpretation of Raspail’s novel, but a reflection on what it revealed, what has since come to pass, and what may yet be averted—if the will to defend can still be rekindled amid the ruins.

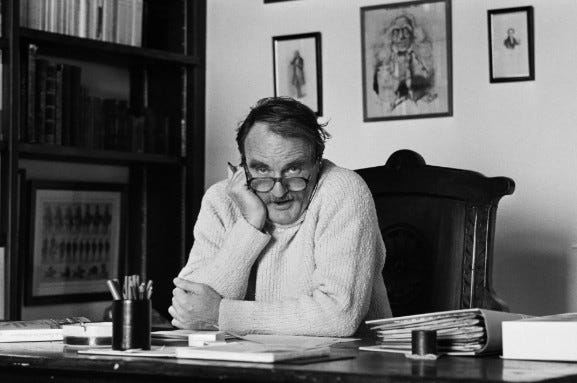

To understand that vision, one must understand the man who saw it. Jean Raspail was not merely a novelist, but a man shaped by history, anchored in tradition, and animated by a fierce fidelity to the soul of France. Born in 1925, into a nation still scarred by the Great War and on the threshold of an even greater one, he belonged to the last generation of Frenchmen who could recall the old France: Catholic, aristocratic, confident in its identity, and still unmistakably its own. His writing, like his life, reflected the belief that the West was not merely a location on a map but a civilizational inheritance, handed down through blood, language, and memory, not conjured into being by bureaucratic decree or by the endless mélange of ever-growing and ever-emptier progressive bromides.

Long before The Camp of the Saints earned him both condemnation and acclaim, Raspail had established himself as a celebrated travel writer and novelist. He traversed the Americas, retraced the paths of forgotten peoples, and followed the routes once walked by the martyred missionaries of New France. His novels—Welcome Honorable Visitors, Septentrion, Who Will Remember the People, and Sire—carry the same elegiac grandeur as Camp, portraying cultures on the edge of extinction and civilizations too noble, or too weary, to defend themselves. His worldview was unmistakably shaped by Catholic sensibilities, royalist loyalties, and an ethnocultural realism long cast out of polite discourse in the postwar order.

He defied easy classification within modern political categories. Though he was awarded the Légion d'honneur by the French government in 2003, Raspail remained at odds with the Republic’s reigning orthodoxies. He believed in nations as organic entities, not ideological constructs; in belonging rooted in lineage and land, not in legal fiction. He rejected the cult of multicultural integration, the dogmas of racial interchangeability, and the bureaucratic fantasy that identity can be manufactured by forms and oaths. And as the future he had foreseen in 1973 began to materialize, from the restive banlieues to the migrant flotillas off Lampedusa, he spoke truths others dared not name. In 2004, when prosecuted by an anti-racist group for voicing concern about France’s demographic future, he responded with clarity: “I have lived in France for 1,500 years,” he declared, “and I do not want it to change.”

That statement has grown only more poignant with time. It was not merely an act of defiance, but an affirmation of continuity: a refusal to forget what France had been, and to reject the lie that its erasure was natural or just. Raspail saw what others could not, and wrote what even fewer had the courage to say. Though he died in 2020, just weeks shy of his ninety-fifth birthday, his most controversial novel has not faded. It has only grown more urgent, as the Western world drifts ever closer to the precipice.

Its premise is simple. Its meaning is not. On its surface, The Camp of the Saints recounts a single catastrophic event: a flotilla of decrepit ships, carrying nearly a million impoverished migrants from India, sails toward the southern coast of France, demanding entry. But to describe it as a story of borders and boats is to miss its deeper intent. Raspail did not simply imagine a migration crisis; he composed an allegory of the modern West, revealing its psychological fragility, disoriented elites, paralyzed institutions, and fatal inability to distinguish friend from foe.

The novel begins with a scene of eerie stillness. An aging professor, alone in his ancestral home overlooking the Mediterranean, watches the approaching armada through a telescope. Night is falling. On the beach, the military burns the corpses washing ashore. Across every radio station, Eine kleine Nachtmusik plays—a light and elegant serenade composed by Mozart, long emblematic of the classical European spirit. The music is not incidental; it is a farewell, a funeral dirge for a Europe of refinement and order, whose cultural echoes will linger even as its people, blinded by moral vanity and immobilized by their own ideals, march calmly toward self-extinction.

From there, the narrative proceeds not with urgency or alarm, but with paralysis. Politicians hold hearings. Bishops preach. Intellectuals craft odes to the intruders. Schoolchildren are assigned essays praising the invaders. Celebrities organize airlifts of incense, sitars, erotic books, and other tokens of decadence. A wealthy Maltese princess flies in to embrace the “poor dears,” only to be met with indifference and contempt. The migrants, once romanticized as helpless refugees, reveal themselves as scornful conquerors, amused by the West’s eagerness to submit.

As the fleet draws near, the mask slips. French citizens quietly flee. What they affirm in public—equality, remorse, solidarity—they discard in private. But no one dares break the spell of silence. The ruling class, hollowed out by decades of ideological fatigue, can neither speak plainly nor act decisively. The military is ordered to stand down. The only resistance comes from a tiny band of armed civilians, swiftly crushed by the very regime that refused to confront the threat. France falls. The West follows. The novel ends with waves of migration engulfing the continent. The “Endless Night” descends.

The novel’s symbolic power lies in its systematic inversion of meaning. Every moral authority behaves immorally. Every act of compassion conceals cowardice. Every institution designed to protect instead enables dissolution. The poor, once subjects of care, are reimagined as vehicles of conquest. Raspail’s insight is that liberal democracies, stripped of loyalty to their own people, turn against themselves under the guise of virtue.

Even the grotesque is purposeful. The leader of the migration is a feces-handling outcaste named Turd Eater, accompanied by his malformed, cadaverous child. Their presence is not merely shocking; it is the spiritual and biological disorder of the modern West made visible. The image is obscene because the truth it gestures toward cannot be spoken aloud: the West was not overthrown, but walked willingly into its own undoing, having lost the will to draw lines or affirm order.

In this sense, The Camp of the Saints is not a plot-driven novel but a lament for a dying civilization. The characters are archetypes, representing betrayal, confusion, courage, and fidelity. The narrative is less a progression of events than a reflection of a civilization’s internal decay. The book poses a question the modern mind cannot tolerate: what if death is chosen, not imposed? What if collapse masquerades as compassion?

Its real offense, to critics, lies not in its racial frankness but in its moral precision. It shows that ruin can be slow, incremental, and self-justifying. It unfolds through a sequence of well-intentioned surrenders, each cloaked in the language of progress. And it leaves the reader not with any sense of finality, but with a haunting question that Raspail poses again and again: “Could that, perhaps, have been one explanation?”

The Camp of the Saints is not simply a dystopia. It is a literary prophecy of what would later be called le Grand Remplacement, or The Great Replacement in English—a term coined by the French thinker Renaud Camus. It refers to the demographic, cultural, and spiritual substitution of the West’s native peoples by foreign masses, justified by ideologies of guilt and equality, and carried out by a ruling class that praises universality while recoiling from roots, limits, and identity. Raspail never used the term, not only because it had not yet been coined, but because he did not need to. His narrative enacts the slow-motion disinheritance of a continent, not by invasion but by invitation; not through conquest but through surrender.

When the novel first appeared, France’s transformation had only just begun. The Algerian War had ended a decade earlier. The pieds-noirs, ethnic French settlers in Algeria, had fled North Africa en masse, while migrants from the former empire arrived under the banners of economic growth and humanitarian concern. A nation once defined by ancestry, land, and faith began to redefine itself through bureaucratic abstractions. Citizenship became paperwork. Frenchness was reimagined as a moral attitude. Borders became a source of shame. Raspail saw farther than his peers. The problem was not merely immigration. It was a profound moral inversion, a civilization taught to celebrate its own disappearance.

This is what separates The Camp of the Saints from cruder portrayals of Western decline: works that trade seriousness for spectacle and, more often than not, descend into ideological pornography. Raspail’s novel is far more dangerous because it is far more honest. There are no conspiracies, no shadowy villains pulling strings behind the curtain. There is no fantasy of racial vengeance. What he offers instead is a devastating account of liberal modernity devouring itself—a world so terrified of moral condemnation that it cannot even rouse itself to defend its own young.

To the casual reader, the novel’s premise may seem implausible: that one migrant fleet could precipitate the collapse of a continent. But its credibility rests not in military logistics, but in the psychological fragility it lays bare. Every institution plays its part. The press canonizes the arrivals. The Church proclaims them redeemers. Schools teach children to love their own erasure. Elected officials wait for someone else to speak first, paralyzed by fear of denunciation.

The allegory is not confined to France. Raspail’s warning applies across the Western world, from Sweden to California, from England to Quebec. The mechanisms are the same: manufactured guilt, elite betrayal, moral cowardice, and the belief that goodness consists in submission. The phrase “camp of the saints,” drawn from the biblical Book of Revelation, becomes a final symbol of indigenous civilization—encircled, outnumbered, and betrayed from within by those who worship the act of opening the gates.

In the new global order, a people that refuses to affirm its own being is treated as illegitimate. European man, in this vision, is no longer one among many. He is the impediment to be erased, the reminder to be shamed, the barrier to be dissolved in the name of abstract fraternity. Raspail’s novel makes clear what this means: the sacrifice not of domination, but of continuity; not the loss of colonies, but the loss of home.

And yet, beneath its despair, the book retains a form of integrity the modern age seeks to extinguish. It dares to pose the outlawed question: What if your highest obligation is to your own kin? What if preservation matters more than praise? What if refusal is the last holy act?

This is what makes The Camp of the Saints unendurable to the liberal mind. It exposes the illusion of universalism, the cruelty concealed within humanitarianism, and the spiritual vacancy behind progressive pieties. In a world ruled by race-blind dogma, Raspail committed heresy, and for that, he will be remembered long after the pious forget him.

Of all the institutions indicted in The Camp of the Saints, perhaps the most damning is not the press or the presidency, but the Church. For Raspail, who remained a devout, if disillusioned, Catholic until the end of his life, the transformation of Christianity was not merely a symptom of Western decline, but its theological engine. Once the guardian of Europe’s sacred order, the Church had, by the late twentieth century, become a vessel for secularized morality—one that demanded self-abolition in the name of compassion. In Raspail’s vision, the Church does not resist the invasion; it sanctifies it, blessing the dissolution of the West with the zeal of a convert and the authority of a tradition it no longer defends.

The fictional Pope Benedict XVI—unrelated to the real former German pontiff who resigned in 2013—is portrayed as a Brazilian universalist, a sentimental cleric whose allegiance is to mankind rather than to God. Under his rule, Vatican III has replaced creed with emotion and doctrine with democratic platitudes. The Eucharist becomes a stage prop, wielded by pacifist monks who confront a sea of invaders with nothing but a monstrance and a prayer. Raspail’s symbolism is precise: the West’s most venerable spiritual institution has become a parody of itself, performing sacred rites whose meaning it no longer grasps, and offering love only to those committed to its destruction.

This Church is not corrupt in the vulgar sense. It is not driven by vice or greed, but by a deeper perversion: the betrayal of its own mission through pity. This is no longer the faith of Lepanto or Charles Martel. It is a gospel of the borderless, a liturgy of abasement. No longer a bulwark, it opens the gates and hands over the keys.

This is not parody, but theology inverted. Raspail understood that no civilization can endure once its highest spiritual institutions consecrate their own dismantling. The new gospel proclaims that the poor are holy by virtue of their need, the foreigner sacred by virtue of his difference, and the strong guilty by virtue of their strength. What was once a hierarchy oriented toward transcendence becomes a creed of self-erasure, a faith of weakness clothed in the language of love. No non-European culture has ever preached such a doctrine, much less attempted to live by it.

Yet Raspail’s indictment is not atheistic. He does not mock the sacred; he mourns its betrayal. His vision is not Nietzschean but Augustinian, a recognition of disordered love, of grace corrupted, and of the need for spiritual order rooted in truth. God does not demand the dissolution of peoples, nor does He bless nations that abandon their sons to chaos. As Raspail reminds us, “God helps those who help themselves,” and no divine hand will intervene for those who will not rise to defend their own.

Thus the Church becomes the ultimate symbol of civilizational decay: truth replaced by sentiment, hierarchy by emotionalism, identity by universal abstraction. The “new theology” in The Camp of the Saints mirrors modern human rights discourse. It is, at bottom, a theology of surrender—stripped-down, secularized, and wielded not to uplift the faithful, but to dissolve the faithful as a people.

Raspail foresaw it all: clerics blessing the migrant ships, bishops decrying border enforcement, pontiffs weeping for strangers while their own flocks were devoured. He saw Christ recast as a symbol of the Global South, and Europe’s crucifixion praised as moral progress. The Church, once the fortress of the West, is rendered in his novel as its doorman.

The death of the sacred, the flattening of moral hierarchy, is perhaps the most tragic dimension of Raspail’s story. Without the transcendent, there is no limit, no defense, no higher calling. There is only sentiment. And as Raspail shows, sentiment alone cannot sustain a civilization. It can only mourn its passing.

Beneath the imagery of ships and the increasingly hollow moral slogans, The Camp of the Saints reveals something deeper: a conviction, now internalized, that Western existence itself is unjust. At its core, the novel is a study of psychological collapse. It does not ask how invasion occurs, but how a people comes to believe that resistance is wicked, that survival is selfish, and that dissolution is virtuous. For Raspail, the answer is clear—guilt.

The disease is not political, nor even demographic. It is spiritual. The West in his novel is not overwhelmed by force of arms, but by a moral infection: a belief that power is inherently abusive, that boundaries are acts of exclusion, and that prosperity is something to be atoned for. The invaders do not storm the gates; they are waved in. The Westerner has already convinced himself that to close them would be a sin.

This condition did not appear ex nihilo (from nothing). As Raspail hints, it is the delayed result of centuries of ideological and theological drift. Christianity, once the animating force of Europe’s identity, had by the twentieth century inverted its own moral compass. The God who once summoned crusaders now appears as a spectral presence on television, weeping over third-world suffering. It is no longer compassion that defines the West’s ethic, but the worship of weakness—the belief that to suffer is to be righteous, and to thrive is to be guilty.

The Church may have planted the seed, but it was secular ideologies such as liberalism, Marxism, and humanitarianism that transfigured guilt into policy. The result is a catechism of decline: multiculturalism, mass migration, open borders, the cult of the refugee. Pride in heritage is now a crime, and continuity suspect. The desire to persist is rebranded as hate.

Raspail illustrates this with withering precision. The elites do not merely permit the invasion; they exalt it. They fund it, moralize it, eroticize it. They baptize the intruders in messianic language, proclaiming them redeemers who will cleanse the sins of whiteness, colonialism, and civilization itself. In this world, charity becomes masochism, and justice becomes vengeance against the native. To defend one's own is to be evil.

The masses, for their part, do not revolt. They vanish. They murmur what they dare not say aloud. They wait for someone else to act. But no one does. The paralysis is mutual. And in the silence, cowardice becomes systemic.

This is not ignorance. It is fear: fear of moral condemnation, of being called racist, of being compared to ghosts from times past. Careers, reputations, and livelihoods hang in the balance. The entire moral architecture of the West has been weaponized against its own people. In such a world, to survive as a European is to risk social death.

Raspail, more than any contemporary author, revealed the fundamental truth: civilizational collapse begins not with external assault, but with internal renunciation. Once a people believes that its history is evil, its power illegitimate, and its future unworthy, the rest is bureaucracy. The spirit abdicates, and the machinery of decline fills the void.

This is the true horror of The Camp of the Saints: not that the West is being overrun, but that the falsehood masquerading as modern culture longs for its own undoing. Not that its enemies are powerful, but that its protectors are ashamed. Raspail offers no solutions. He knew the sickness ran deeper than law or policy. It is a metaphysical disorder, and it demands a spiritual reckoning—a new moral beginning rooted in identity, memory, and the rebirth of sacred limits.

Until that moment comes, the ships will keep coming. And the gates will remain open, not by compulsion, but by unbelief.

This, Raspail understood. He was not merely chronicling decline; he was identifying its root. The Camp of the Saints does not ask why the Third World advances on Europe. It asks why Europe, fully aware of the stakes, refuses to stand its ground. Every Western leader in the novel recognizes the future—rising crime, social fragmentation, biological disorder—yet none take action. Why? Because no one wants to be first. No one is willing to be hated. No one believes they are permitted to wield authority in defense of their own.

Raspail makes clear that the crisis is not one of strength, but of conviction. France still possesses an army, a press, a governing class, and a native majority. Yet when the armada appears, these forces do not unite, they neutralize one another. The President turns in desperation to a nationalist publisher, imploring him to speak the truth that officialdom cannot. The military awaits orders that never arrive. Bishops mutter platitudes. Journalists drift with the cultural breeze. All are paralyzed. Not by the foe at the gate, but by fear of being condemned for closing it.

In this world, courage is isolated and suicidal. Most citizens loathe what is unfolding, as they not only see its consequences but experience them directly. Yet each hopes that someone else will act first. Those who speak out are crushed, mocked, erased, or ruined. The rest take the hint and fall silent. No one wants to be a martyr to a cause that no one dares name. In such an environment, cowardice becomes contagious. And betrayal takes root, not because the people approve, but because they believe resistance is futile.

Even armed defiance proves fragile. The novel’s titular “camp” is not an army, but a handful of Frenchmen who make a final stand, only to be obliterated by their own military, now loyal to the post-national regime. The symbolism is brutal: the West will eliminate its last defenders rather than shatter the illusion of virtue. The sacred lie must survive, even if truth, and those who carry it, must perish.

Raspail understood that collapse is never spontaneous. The Left triumphs not by force of argument, but by occupying the void left by a Right that refuses to act. There is no Caesar waiting in the wings, no general with a secret plan, no deliverance at the final hour. There is only a disoriented people, a cowardly elite, and a handful of loyal men left to be sacrificed. His vision is not merely bleak, but structural. Good intentions mean nothing. Markets will not save the West. Survival requires leadership, and leadership requires the will to suffer.

The characters in The Camp of the Saints are not ignorant. They are articulate, perceptive, and well-informed. But knowledge does not translate into action. The nationalist publisher Jules Machefer emerges as a tragic figure—one who sees clearly, anticipates the danger, waits for the decisive moment, and then, when it arrives, stands still. Not out of confusion, but out of conviction that it is already too late. His realism is exact, but it amounts to a final, lucid form of surrender.

Here Raspail unmasks the Right’s central flaw: the hope that history will wait. That conditions will improve. That someone else will give permission. But the world does not awaken to caution. What is required is not approval, but authority; not the reassurance of polls, but the clarity of vision; not the comfort of consensus, but the readiness to accept sacrifice.

The true tragedy of The Camp of the Saints is not that France is invaded. It is that she submits. Not by force, but by choice. Her final institutions—church, school, media, government—are not overtaken from outside. They rot internally, relinquishing their authority, abdicating their duty, and sanctifying their own extinction. And when a few men rise to defend the nation, it is the government itself that moves to crush them, acting not in the name of the people, but in service of an ideology that no longer believes the nation should exist.

What makes the novel so unbearable, and so prophetic, is that it forces a confrontation modernity cannot endure: that civilizational death is not imposed from without, but embraced from within. The fleet sails not because the enemy is strong, but because the ramparts stand empty. The invasion succeeds not by force, but by surrender. It occurs not out of necessity, but out of shame.

And yet, the very act of naming this betrayal is a beginning. For those willing to remember who they are, to reject the lie that love means erasure, and to affirm the beauty of their inheritance, the future is not yet lost. Europe still lives, the West still lives—in blood, in stone, in memory—and wherever her sons choose fidelity over fear, the ramparts rise again.

Back in the 1980s, as a small publisher in Australia, I wanted to reprint it here. But one of the 'usual suspects' in New York put the boots into that idea.

Now Australia is being inflicted with mass immigration by its proto communist government. And the descent into the Inferno is well on its way.

Am I allowed to say this book was read on Pete Quiñones’s Substack? If anyone wants to hear it read piecemeal.