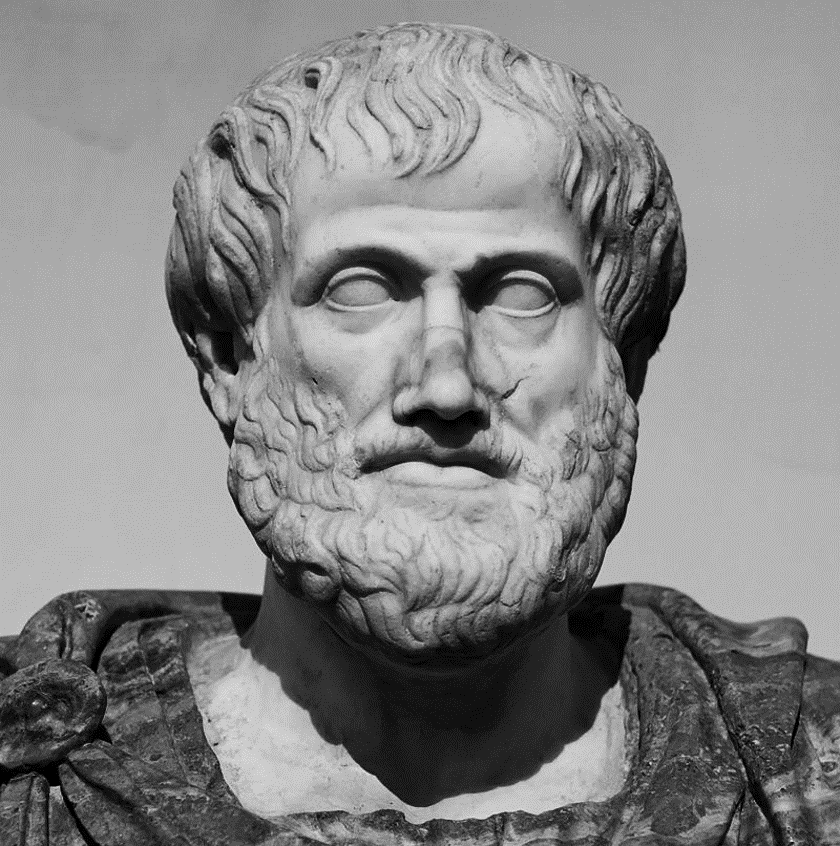

The Laws of Life: Aristotle and the Biopolitical Foundations of the Polis

How the Ancients Governed Blood, Virtue, and Memory to Sustain Civilization

I. Biopolitics and the Nature of the Polis

The term biopolitics is most often associated with Michel Foucault, the leftist post-structuralist who sought to deconstruct the nature of power and governance, particularly how modern states manage life through diffuse systems of control, bureaucratic oversight, and institutional surveillance in an increasingly complex Western world. He analyzed the mechanisms through which the modern state apparatus operates—demographic regulation, social discipline, administrative rationality—but refused to ask the deeper question: what purpose should political power serve, and to whom is it accountable?1 His analysis remained confined to critique, detached from any moral or civilizational foundation. What he called biopower, the ancients would have called responsibility. Where he saw domination, our forefathers saw duty.

In short, Foucault recognized the structure of modern governance, but not its purpose. He gestured toward the machinery but avoided the telos—the guiding end toward which political life must be directed. For him, biopolitics was a historical symptom; for the ancients, it was the heart of statecraft. It is no accident that a wide range of ancient figures—Aristotle and Plato, Lycurgus and the early lawgivers—placed the governance of life, including questions of marriage, reproduction, and belonging, at the very center of political order.

As such, the roots of biopolitics run far deeper than the twentieth century. They reach back to classical antiquity, when the state and the household were understood as extensions of a single organic order. The Greeks did not theorize biopolitics; they lived it. They legislated marriage, regulated reproduction, honored ancestral lineage, and conceived of the city not as a neutral apparatus for administering rights but as a living body tasked with protecting, refining, and transmitting a people across generations.

A nation begins where blood is remembered and order is forged by a people conscious of their ancestral continuity. This is biopolitics in its truest form—not an abstract theory, but a governing instinct, among the oldest and most indispensable foundations of political life. It is the art and science of shaping a people not only through laws and institutions, but through the cultivation, regulation, and preservation of their biological, moral, and cultural character. It concerns itself with birth and death, with kinship and inheritance, with the enduring question of who belongs and who does not. The state, in this vision, is not a contract or abstraction, but a living order, nurtured by custom, shaped by blood, and directed by nature toward excellence and continuity.

In ancient Greece, this vision was not speculative. It was embedded in religion, ritual, and law. The city was not merely a jurisdiction, but a sacred extension of the ancestral household, formed for the sake of virtue, sustained by reverence for the dead, and animated by duty to the unborn. Nowhere was this more fully articulated than in the thought of Aristotle.

Herodotus gave voice to the first Western notion of citizenship. In The Histories, he describes the Greeks as united not by territory or government, but by shared blood, language, worship, and way of life.2 Their identity was rooted in descent and memory, a bond that transcended political boundaries and grounded civic unity in ancestral belonging.

Aristotle gave this instinct philosophical form. In his Politics, he offers the clearest expression of biopolitical order in the Western tradition. The polis, he tells us, is the highest form of human association, not because it guarantees liberty or material comfort, but because it allows man to fulfill his nature as a rational and political being.3 “Man is by nature a political animal,”4 not in the modern sense of individualistic or atomized participation in politics, but because he cannot achieve his telos—his natural end or perfection—outside the city. Just as the acorn is meant to become the oak, man is meant to become a citizen, a legislator, a philosopher. And the polis is the soil in which this transformation takes root.

For Aristotle, political life is the culmination of biological life. The city is not constructed above or against nature, but in harmony with it. Its laws must reflect the natural hierarchy of ability, character, and purpose, mirroring the order of the cosmos. The Greek word κόσμος does not simply mean “universe,” but “order,” a structured totality in which each part fulfills its proper role. Aristotle envisions the city as a finely tuned organic community, composed of those who are biologically, morally, and intellectually suited to share in its burdens and responsibilities. “The prime factor necessary in the equipment of a city is the human material,” he writes, “and this involves us in considering the quality as well as quantity.”5 Citizenship is not a universal entitlement, but a sacred inheritance, earned through descent, virtue, loyalty to the common good, and lived participation in the life of the polis.

Accordingly, Aristotle defines the citizen not by legal status, but by ancestry and function. “A citizen is one born of citizen parents on both sides.”6 Foreigners could occasionally be naturalized, but always “in some special sense,”7 and never as equals to those whose lineage embodied the community itself. Law may accommodate outsiders, but it cannot fabricate belonging. The biological and the political converge in this conception: a healthy city depends on the reproduction of a healthy citizenry.

This is why Aristotle, like the Greek world more broadly, insisted that reproduction was not a private matter, but a public and sacred obligation. The Indo-European religion underlying Greek law regarded celibacy as impious and placed the continuation of the family line above all private desire. The father ruled for the good of the household, and the city extended that rule into the public sphere. To govern rightly meant shaping not only institutions, but the bodies and souls of the people. “It is likely,” Aristotle writes, “that good sons will come from good fathers, and that the appropriately raised will be of the appropriate sort.”8

This is biopolitics in its ancient and proper sense: the governance of life ordered toward the perfection of man. Aristotle does not speak of equality or rights. He speaks of the city as a whole, bound by duty, formed by custom, and animated by shared blood. “The goodness of every part must be considered with reference to the goodness of the whole.”9 And again: “A whole is never intended by nature to be inferior to a part.”10

To speak of Aristotle’s politics is to speak of the biology of the city, its inner harmony, its continuity, and its need for exclusion. The state is not a warehouse of individuals, but a living form, sustained by memory and transmitted through descent. Its purpose is not to gratify appetites, but to elevate the noble, to discipline the base, and to cultivate man’s highest faculties. In this, Aristotle presents not a tyranny, but a vision of civic life that is concrete, hierarchical, and alive.

II. Citizenship, Kinship, and the Structure of the Ancient City

To understand Aristotle’s conception of the biopolitical, one must begin with his conviction that the city is not a mechanical arrangement imposed upon disparate individuals, but a natural extension of the household. “The polis,” he writes, “is an association of households and clans in a good life, for the sake of attaining a perfect and self-sufficing existence.”11 The city does not arise from contract or convenience, but from bonds already forged—bonds of blood, of religion, and of ancestral memory. The lawgiver does not invent the people. He inherits them, refines them, and secures their unity through education, tradition, and law. That unity rests, above all, on descent.

A citizen, for Aristotle, is not defined by geography or legal compliance, but by participation in the life of the city. Citizenship means both ruling and being ruled. But this participation presupposes belonging. The members of a polis must recognize in one another a shared inheritance. They must be capable of philia, civic friendship, grounded in common ancestry and collective duty. Greek cities therefore limited citizenship by birth, often requiring generations of citizen parentage. The city was not a gathering of strangers but a communion of extended families, each bound by sacrificial ties to land, law, and lineage.

Kinship, then, was not a private sentiment. It was a political principle. The natural affection between parent and child, which Aristotle describes as loving “a sort of other self,”12 served as the model for civic unity. Brotherhood within the household extended into solidarity within the city. This bond could not be manufactured by decree or ideology. It was the product of shared blood, common rituals, and inherited responsibilities. Expressions such as “of the same stock” and “of the same blood” were not poetic metaphors but foundational truths of political order.

This emphasis on descent explains Aristotle’s warnings about foreignness and faction. Throughout his Politics, he records how cities fell into stasis, civil strife, after granting citizenship to outsiders. In every case, from Magna Graecia to the Aegean, immigration without deep assimilation led to conflict. “Heterogeneity of stocks may lead to faction,” he cautions, “at any rate until they have had time to assimilate.”13 Even then, unity forged by blood and time could be shattered by political decisions that enfranchise those with no roots in the civic body.

Aristotle’s concern with cohesion extended also to the actions of tyrants. Despots, unlike kings, relied not on loyal citizens, but on foreigners. “Kings are guarded by the arms of their subjects,” he notes, “tyrants by a foreign force.”14 A tyrant severs the organic bonds of family, cult, and tradition because those bonds generate loyalty, resistance, and memory. A people who know who they are cannot be easily ruled by those who seek to remake them.

This same insight guided Aristotle’s understanding of the household. The family was not merely a private unit but the seed of the state. Within it, man first encountered duty, hierarchy, and order. The father ruled not as a despot, but as a moral exemplar, guiding his household through seniority, wisdom, and affection. Just as the king should embody the soul and blood of his people, so too must the father embody the legacy of his line. Political order required the preservation of the familial structure. That is why both tyrannies and modern ideologies have sought to weaken or dissolve it.

For Aristotle, the bonds of household, kin, and citizen form a seamless structure. The polis was not an aggregate of laws or an abstract collection of rights. It was a body shaped by time, memory, and descent. It requires shared identity to produce loyalty, and shared virtue to preserve order. When these foundations are undermined—by mass immigration, atomizing ideologies, or the collapse of the family—the city ceases to exist in anything but name. No legislation, however wise, can sustain a people once the blood and spirit that bind them have been forgotten or replaced.

III. Law, Education, and the Reproduction of the Citizenry

In Aristotle’s political philosophy, law is neither a neutral contract among individuals nor a mechanism for balancing competing interests. It is the formative instrument of a people’s soul. The lawgiver does not merely restrain injustice; he molds character, instills virtue, and ensures the continuity of a distinct moral and biological order. “All would agree,” Aristotle writes, “that the legislator should make the education of the young his chief and foremost concern.”15 Education, in this context, is not the accumulation of knowledge but the shaping of habits, loyalties, and embodied excellence within a given way of life.

That way of life depends upon the quality of the citizenry. Aristotle makes no effort to obscure this. Population policy, for him, is not secondary but foundational. “The prime factor necessary, in the equipment of a city, is the human material,” he insists. This means the statesman must consider both the quality and quantity of those who compose the body politic. The city is not defined by its borders or institutions but by the nature of the people who sustain it—a people bound by blood, animated by reason, and ordered toward flourishing. Its limits are drawn not by bureaucracy, but by kinship, virtue, and the capacity for civic excellence.

Citizenship, then, must rest on lineage. Aristotle affirms what the ancient world took as self-evident: a citizen is one born of citizen parents, often over multiple generations. The biological foundations of the polis are reflected in its rituals, its marriage laws, and its structure of governance. The city is, in essence, an extended household. Laws exist not to equalize individuals but to preserve the inherited form of a people across time. Naturalization, when it occurs, is rare and deliberate—an act of statecraft, not sentiment.

This framework gives rise to a deeply Aristotelian view of reproduction: not as a private decision, but as a public responsibility. Men and women, he argues, “render public service by bringing children into the world,”16 and this service must be aligned with the needs of the city. Aristotle prescribes ideal marriage ages: thirty-seven for men, eighteen for women, and warns against the physical and moral decline that results from poor timing or neglect. Even pregnant women are to maintain strength and discipline, as he believed the mother’s health directly shaped the child.17 The body itself becomes a site of civic duty.

Aristotle does not shy away from the harder implications of this position. He endorses legal prohibitions against raising deformed children,18 a position widely accepted in the Greek world. This was not regarded as cruelty but as prudence—a way of securing the long-term strength of the city by preventing the rise of a dependent and unfit population. Overpopulation, too, was seen not as an abstract issue, but as a direct threat to social order. Too many children could lead to poverty, class instability, and civic decay. “Regulation of the amount of property ought to be accompanied by regulation of the number of children in the family.”19 The household and the city must be governed by the same principle: measured order directed toward excellence.

Reproduction, then, is inseparable from law. The lawgiver is not a mere administrator. He is a craftsman who shapes the very substance of the city—its virtues, its demographics, its continuity. What kind of people will the city contain, and what virtues must they be shaped to embody? These are not marginal questions for Aristotle. They are the essence of political life.

This is the heart of his biopolitical vision. The state exists not to protect the preferences of atomized individuals, but to form and preserve a people worthy of self-rule. Its purpose is not freedom as modernity understands it—defined by autonomy, choice, and rights—but responsibility, excellence, and the endurance of the noble. The highest political task is not to secure liberty but to cultivate greatness in the souls of a people bound together by ancestry, law, and memory.

IV. The Fragility of Order: Diversity, Decadence, and the Loss of the Polis

Aristotle, like Plato before him, understood that the gravest threats to political order arise not from foreign invasion, but from internal decay. Virtue erodes. Ancestral bonds weaken. Foreign elements, once admitted without assimilation, destabilize the very soul of the city. The polis, though rooted in strength, is never immune to corruption. In Aristotle’s analysis, decline often begins with the careless extension of citizenship, the rise of factionalism, and the seductive promise of equality detached from nature.

At the heart of his warning lies a simple principle: solidarity requires similarity. “Every difference,” he writes, “is apt to create a division.”20 The polis was more than a political structure. It was a shared culture, a kinship order grounded in blood, language, and worship. When this cohesion was disrupted by mass immigration, foreign rule, or tyrannical manipulation, conflict inevitably followed. Aristotle recounts, with empirical precision, how cities fell into stasis or civil war after admitting outsiders. “A city cannot be constituted from any chance collection of people,” he observes, “or in any chance period of time.”21 Civic identity is not a bureaucratic label. It is an inheritance.

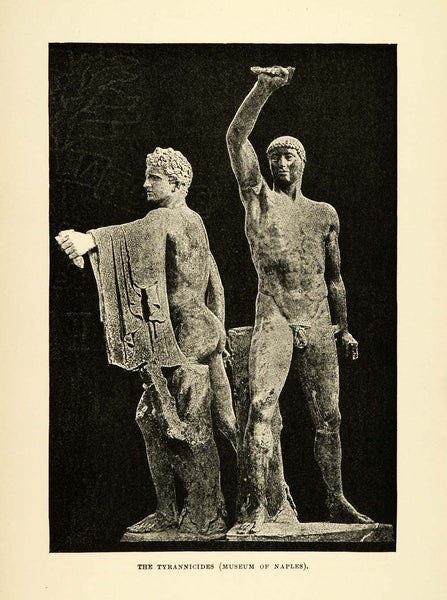

Tyrants understand this well. Unlike citizens, foreigners have no attachment to the city’s founding myths, laws, or ancestral cults. They are tools of power, not members of a body politic. “Kings are guarded by the arms of their subjects,” Aristotle writes, “tyrants by a foreign force.”22 The tyrant fears the citizen, who carries memory and pride. To rule without resistance, he must sever those ties—dissolve the tribes, silence the ancestral rites, enfranchise the alien, and weaken the family. “Every contrivance,” Aristotle warns, “should be employed to make all the citizens mix as much as they possibly can, and to break down their old loyalties.”23 In this, tyranny and radical democracy converge.

Aristotle does not reject constitutional rule. On the contrary, he praises the politeia, the mixed regime, as the most balanced and enduring. But when democracy ceases to serve the common good and begins to gratify base appetites, it undermines its own foundation. “There is a false conception of liberty,” he writes, “the result of which is that in these extreme democracies, each individual lives as he likes.”24 This is not liberty in the classical sense, which is bound to law and virtue. It is license: freedom without form, autonomy without obligation. It severs the natural ties between man and man, father and son, citizen and city. It is the end of the political.

This descent into decadence is not accidental. Prosperity can be more corrosive than hardship. “People are easily spoiled,” Aristotle warns, “and it is not all who can stand prosperity.”25 He draws particular attention to Sparta. Victorious in war, it became decadent in peace. Wealth weakened discipline. Women, unrestrained by law, gained disproportionate influence. The martial ethic gave way to softness, and internal division followed. The lesson is clear: law cannot save a people who no longer govern themselves.

Athens provides a similar case. After the expulsion of the tyrants, Cleisthenes enrolled foreigners and even slaves into the civic tribes.26 These reforms, aimed at consolidating popular power, dissolved the inherited foundations of civic identity. When all distinctions—of birth, of virtue, of loyalty—are erased in the name of equality, the result is not harmony, but chaos. “Justice,” Aristotle writes, “is assumed to consist in equality and equality in regarding the will of the masses as sovereign… this is a mean conception. To live by the rule of the constitution ought not to be regarded as slavery, but rather as salvation.”27 True freedom is not the absence of limits, but life within a just and natural order.

The decline of the polis begins when its nature is forgotten. A city is not a crowd or a marketplace. It is not a stage for opinion or a zone of consumption. It is a sacred form, shaped by discipline, memory, and shared ancestry. It must be guarded not only by armies and courts, but by law, custom, and reverence for the dead. Once those bonds are broken, once citizens forget who they are and why they exist, the city becomes a husk. It loses its soul and becomes vulnerable, whether to tyranny from within or absorption by empire from without.

V. The Lawgiver and the Revival of Order

If the polis is a living body, ordered by nature and sustained by kinship, then its renewal comes not through reform, but through remembrance. For Aristotle, the hope in an age of decline is not mass participation or ideological revolution, but the emergence of a nomothetēs, a lawgiver capable of restoring order upon its rightful foundation. In this vision, law is neither a bureaucratic instrument nor a shifting consensus. It is a sacred inheritance, a structure designed to cultivate virtue across generations. Even so, law cannot anticipate all things. “It is easy enough to theorize about such matters,” Aristotle admits. “What actually happens depends on chance.”28

The lawgiver must therefore grasp the limits of rule. Some men transcend the law not by defiance, but by excellence. Like Homeric kings and city-founders, they embody the very order from which law arises: nature, reason, and virtue. “There can be no law governing people of this kind,” Aristotle writes. “They are a law in themselves.”29 Such men do not violate justice by standing above conventional rules. They reveal its origin in hierarchy and measure.

Yet Aristotle does not embrace despotism. His ideal is the politeia, a mixed constitution anchored in law, tempered by aristocracy, and sustained by a virtuous middle class. These are not passive citizens. They are fathers, farmers, warriors, and judges. They hold property not to indulge appetite, but to fulfill duty. Their liberty is not license to act without restraint, but the earned capacity to participate in the life of the city. The politeia expresses the natural hierarchy of ability and character, ordered toward excellence and preservation.

This order depends on education and memory. “The system of education must also be one and the same for all,” Aristotle insists, “and the provision of this system must be a matter of public action.”30 Education is not private, and the citizen does not belong to himself. As a father raises his son to inherit a name and household, so the city must raise its youth to inherit its laws, its spirit, and its purpose. What is passed down is not merely knowledge, but soul. This is not tyranny. It is tradition made conscious and sustained through law.

Yet virtue is fragile. It does not flourish in every condition. Prosperity invites arrogance. Peace invites softness. Aristotle warns against the constant desire for innovation, recognizing that novelty often conceals decay. “War automatically enforces temperance and justice,” he writes. “The enjoyment of prosperity… is more apt to make people overbearing.”31 A stable regime requires more than law. It demands reverence—for ancestral cults, founding principles, and the rhythm of life that binds the living to the dead. Without that reverence, even the best-constructed constitution collapses into emptiness.

In this sense, Aristotle’s Politics is not simply descriptive. It is prescriptive. It gives voice to the deeper instinct of Hellenic civilization: that the city exists not for trade or pleasure, but for aretē, the full development of human excellence. The lawgiver must legislate not for man in the abstract, but for this people, in this soil, with these memories. If he succeeds, his laws will endure not as static decrees, but as living tradition, embodied in the character, habits, and loyalties of those who inherit them.

This is what Nietzsche saw and praised in the Greeks: the aristocratic soul of a people who refused to dissolve themselves into an abstract humanity. They honored strength, beauty, courage, and wisdom not as symbols, but as expressions of a living spirit that resisted decline. They knew that man thrives not in isolation, but within a form that disciplines desire and channels it toward greatness. Civilization was not formless mass, but an organic unity, sustained by sacrifice and law.

From Homer to Lycurgus, from the rites of the household to the doctrines of Politics, the Greek world offers more than an intellectual legacy. It offers a political and biological blueprint for endurance. It rejected egalitarianism and universalism in favor of a rooted, exclusionary, and sacred vision. At its heart, it was biopolitical.

To recover this spirit is not to imitate its outward forms, but to remember its essence and project it into the future. The coming world will not belong to those who preach tolerance, nor to those who place their faith in disembodied systems or technological illusions. It will belong to those who remember who they are, and who possess the will to live, to endure, and to multiply in fidelity to their ancestors and in duty to their descendants.

Aristotle offers no promises of progress. He speaks to the hard laws of life. The city is not a machine. It is a living order, shaped by memory, rooted in blood, and elevated through virtue. The task of statesmanship is to preserve that order through wise law, shared education, and the continuous cultivation of excellence, so that the city may endure, not in comfort, but in greatness.

Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction, trans. Robert Hurley (New York: Vintage Books, 1990), esp. Part Five: “Right of Death and Power over Life.”

Herodotus, The Histories, trans. Aubrey de Sélincourt (London: Penguin Books, 2003), 8.144.

Aristotle, Politics, trans. Carnes Lord (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), 1252b27–30.

Ibid., 1253a2.

Ibid., 1325b33.

Ibid., 1275b22.

Ibid., 1274b38.

Aristotle, Rhetoric, trans. W. Rhys Roberts (New York: Modern Library, 1954), 1366a31.

Aristotle, Politics, 1260b8.

Ibid., 1288a15.

Ibid., 1280b29.

Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, trans. Terence Irwin (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 2019), 8.12, 1161b28.

Aristotle, Politics, trans. Carnes Lord, 1303a13.

Ibid., 1285a16.

Ibid., 1337a11.

Ibid., 1335b26.

Ibid., 1335b11.

Ibid., 1335b19.

Ibid., 1266a31.

Ibid., 1303b7.

Ibid., 1303a13.

Ibid., 1285a16.

Ibid., 1319b19.

Ibid., 1310a12.

Ibid., 1308b10.

Ibid., 1275b34.

Ibid., 1310a12.

Ibid., 1331b18.

Ibid., 1284a3.

Ibid., 1337a21.

Ibid., 1334a11.

“A nation begins where blood is remembered and order is forged by a people conscious of their ancestral continuity”

Incredible line

The city began as a confederation of familial and clannish cults with common tongue, blood, and worship. This is how all nations began and can renew only by returning to the well of memory suffused with wisdom and poetry.