Translator’s Note

Originally published as “La tragedia della Guardia di Ferro romena” (“The Tragedy of the Romanian Iron Guard”) in the newspaper Roma in 1938, this essay by Julius Evola is not merely a political reflection, but a spiritual and symbolic elegy. It records his personal meeting with Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, the founder and leader of the Romanian Iron Guard, and stands as one of the most vivid portraits of the Romanian national-revolutionary movement ever composed by a contemporary observer of its inner essence.

The piece should be read alongside “Colloquio col capo delle "Guardie di Ferro” (“Conversation with the Leader of the ‘Iron Guards’”), which appeared in Regime Fascista on 22 March 1938. Together, these essays mark Evola’s effort to interpret Codreanu not only as a political figure, but as a manifestation of a higher type: the warrior-ascetic in service to transcendent ideals. Evola’s recollection of this encounter remained significant throughout his life, resurfacing decades later in ”Il cammino del cinabro” (“The Path of Cinnabar”) and in “Il fascismo visto dalla destra” (“Fascism Seen from the Right”).

Codreanu’s figure made such an impression on Evola that it provoked comment even within the Third Reich. In a confidential Ahnenerbe (“The Ancestral Heritage Research and Teaching Society”) report dated August 31, 1938, sent to Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, Evola was accused of “exerting pressure on the leaders and officials of the Party and the State” and “developing propaganda in neighboring countries.” The countries in question were France and Romania, where Evola’s presence, writings, and lectures had been closely followed. In Bucharest, he was introduced to Codreanu by Mircea Eliade, who was then a member of the Iron Guard. This fateful meeting took place at the Casa Verde, the “Green House,” the Guard’s spiritual and organizational center, only months before Codreanu’s arrest and assassination by the regime.

As Evola recounts, Codreanu was no mere political leader, but the incarnation of a vision: of the New Man, formed through suffering, discipline, hierarchy, and sacrifice. The essay not only documents Codreanu’s ideas—anti-communist, anti-democratic, anti-materialist, and rooted in national mysticism—but also the tragedy of their betrayal. Evola perceives in the Iron Guard not a mere party, but a spiritual order, oriented toward the regeneration of the Romanian nation through the forging of character and metaphysical alignment with the divine.

It is worth noting that the French translation of this essay, published in Totalité (“Totality”) in 1984, censored several passages concerning Codreanu’s views on the Jewish question, thus rendering Evola’s original analysis incomplete and ideologically defanged. This English edition restores the full integrity of the original text.

This translation preserves all significant foreign terminology, in order to maintain the symbolic precision of Evola’s language. The reader is advised that, as with all of Evola’s writings, this essay presupposes a certain symbolic literacy: a familiarity with esoteric language, Tradition, and the vertical axes of meaning which govern the soul of history.

Adolf Hitler, upon hearing of Codreanu’s murder, ordered all German officials who had received Romanian state honors to return them in protest. As Émile Cioran would later write, “Romania is ruled by the dead Codreanu.” And through Evola’s words, that presence still walks.

Begin.

The car carried us beyond the outskirts of the city, along a long and desolate provincial road, beneath a leaden, rain-sodden sky. It turned sharply to the left, entered a rural path, and came to a halt before a modest villa of austere lines—the Green House, the spiritual and organizational heart of the Iron Guard.

“We built it with our own hands,” said the legionary leader accompanying us, with a quiet pride that bore no trace of vanity.

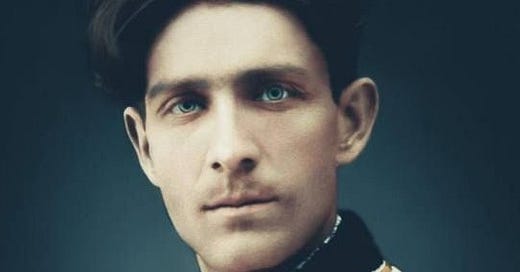

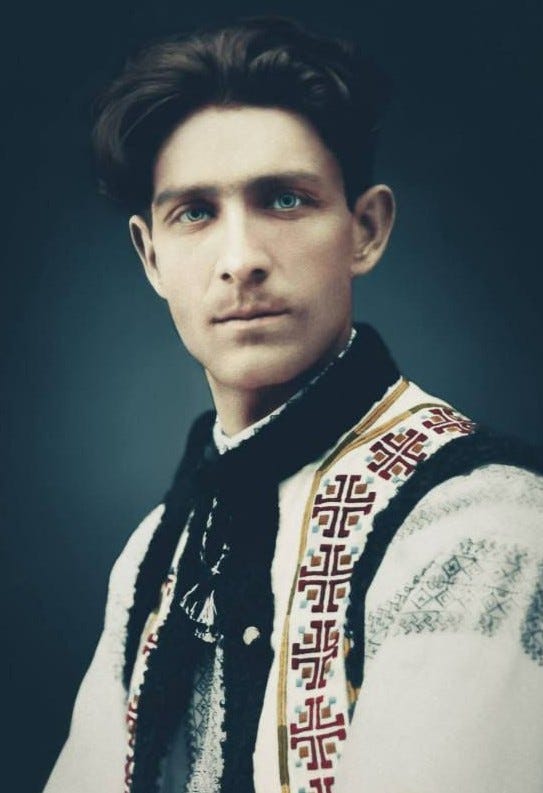

We entered, passed through a kind of guardroom, and ascended to the upper floor. There, parting through a group of Legionaries, came toward us a young man—tall, slender, with a bearing at once noble and ascetic. His face bore the seal of an uncommon frankness and force: eyes of steel-blue, a high and open brow, the unmistakable stamp of the Roman-Aryan type. Yet amid these virile features there shone something else—something contemplative, mystical, inwardly illumined.

This was Corneliu Codreanu: the leader and founder of the Romanian Iron Guard. The man whom the world press, in its chorus of dishonor, brands an “assassin,” a “disciple of Hitler,” a “conspirator and anarch.” And why? Because since 1919 he has stood in unrelenting defiance of Israel and those occult powers, more or less entangled with it, that operate parasitically within the life of the Romanian nation.

Of all the leaders of the national movements encountered in our travels across Europe, few, if any, left upon us so profound and favorable an impression as Corneliu Codreanu. In speaking with him, we discovered a rare accord of principles, the kind found only among those who have severed themselves from the transient and the political, and who have anchored their will to the firmament of the spirit. Rarely have we seen in one man such an unhesitating ascent from the plane of the contingent to that of higher, ontological premises, a will toward national and political renewal rooted in the metaphysical.

Codreanu, for his part, did not conceal his satisfaction at meeting one with whom he could speak beyond the weary banalities of constructive nationalism, that empty phrase so often used to disguise pragmatic reformism or bourgeois opportunism. In us, he found a witness to the deeper essence of legionarism, which is neither political nor economic in its primary substance, but metaphysical, ascetical, and sacrificial.

Our meeting occurred during the tumult that followed the fall of the Goga cabinet, during the intervention of the Crown, the promulgation of the new constitution, and the orchestration of the plebiscite. We had already been informed of the hidden currents beneath this upheaval; Codreanu, in a lucid and crystalline synthesis, confirmed and expanded our understanding.

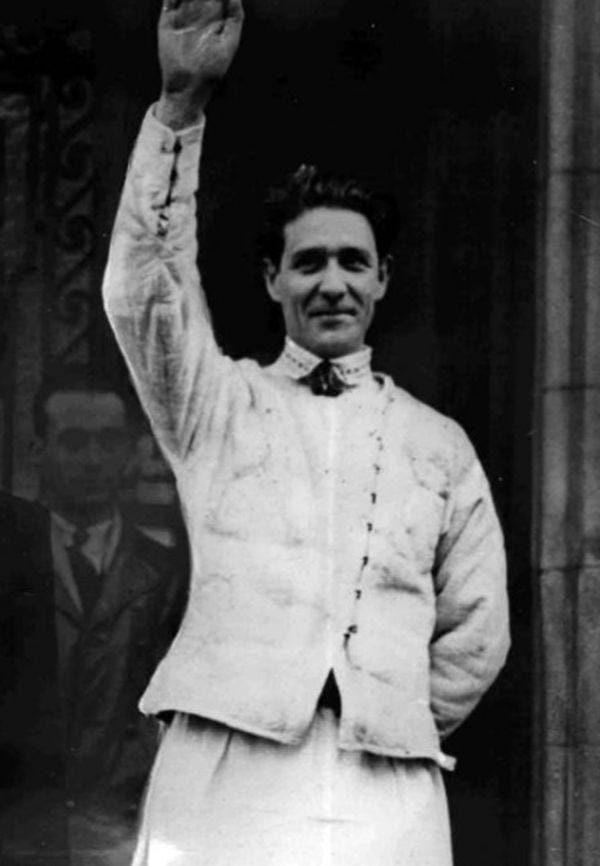

His faith in the future was firm, almost luminous. He believed in the imminent triumph of his movement, and its tactical silence during that critical hour was not the result of passivity, but of deliberate discipline. “Had there been proper elections,” Codreanu told us, “as Goga had intended, we would have emerged with an overwhelming majority. But when confronted with a plebiscite, a fait accompli, a constitution conceived by the King, we chose not to dignify the charade with resistance. We refused to lend legitimacy to the illegitimate.”

He added, with the imagery of the warrior: “We have already seized the first line of trenches, then the second, and the third. And now the adversary, retreating into the false sanctuary of its hidden stronghold, fires upon us blindly, unaware that we desire nothing more than to assist it in destroying the true enemy.”

On the question of monarchy, Codreanu was unequivocal: “We are Monarchists, all of us. But we cannot betray our mission, nor strike pacts with a world that is moribund, corrupt, and contrary to the eternal order.”

When he offered to return us to our inn in his own car, he gave no thought to the stir such an act might cause, and we gave even less to the warning issued by our legation, which had informed us that anyone meeting with Codreanu would be expelled from the kingdom within twenty-four hours. Taking his leave, and aware that we were soon bound for Berlin and Rome, he said to us, “To all those who fight for our cause, I offer my salute and tell them that Romanian legionarism is, and shall remain, unconditionally on their side in the anti-Jewish, anti-democratic, and anti-Bolshevik struggle.”

The Italian translation of Codreanu’s book The Iron Guard, long anticipated in Bucharest, has now been published in the Europa Giovane series (Casa Editrice Nazionale, Rome–Turin, 1938). This volume constitutes the first part of a work that is at once the autobiography of Codreanu, the chronicle of his movement, and a natural unfolding of his doctrine and national program. It may be placed beside the first part of Mein Kampf without hesitation or fear that the comparison will diminish its stature. On the contrary, it is the very severity of Codreanu’s destiny, the tragic force of the events he recounts, that lends his narrative its peculiar power of evocation. No Fascist who seeks to understand the deeper laws of history should neglect this testimony, for in it one finds, transposed onto Romanian soil, a repetition of our own anti-democratic and anti-Jewish revolutions.

Through this book, the truth long obscured and defamed by a servile press is at last brought into the light. One sees clearly that no serious judgment concerning the future of Romania can be made without reckoning with the spirit of the legionary movement. Though outwardly repressed, it is not dead. Its flame persists, hidden yet intact, awaiting the hour of return.

By its very nature, Codreanu’s book resists any attempt at summary. We can only draw the reader’s attention to a few doctrinal and general points that reveal the inner nature of his movement. Already by 1919 or 1920, when he was but a youth of twenty, Codreanu rose against the Bolshevik peril in the name of the Romanian nation. Not with speeches, but with collective action. His deeds mirrored those of our own squadristi: confronting the insurgent workers, tearing down their red banners from the factories, and raising in their place the national flag.

A disciple of A. C. Cuza, father of the Romanian national idea and pioneer of the anti-Semitic struggle, Codreanu had already discerned, with unflinching clarity, the true consequences of a communist triumph. It would not have brought about a proletarian Romanian order. It would have subjected Romania to enslavement under what he called “the filthiest tyranny, the Talmudic, Israelite tyranny.” Israel does not pardon those who unmask it. From that moment, Codreanu became the bête noire of the press subsidized by Israel, the target of a campaign not merely of slander against his person, but of desecration against the sacred idea of nationhood itself.

Of that time, Codreanu writes:

“In one year I learned as much about anti-Semitism as would be enough for three men’s lifetimes. For you cannot wound the sacred convictions of a people, what their heart loves and respects, without causing deep pain and shedding the heart’s blood. It was seventeen years ago, and my heart bleeds yet.”

In that period, Codreanu’s fight was waged against the champions of the red International. His men broke the presses of Jewish newspapers, the same papers that insulted the king, slandered the army, and ridiculed the Church. Yet in time, under the same banners of monarchy, army, and public order, the Romanian press—adept in all the cunning arts of camouflage—would resume the same campaign against Codreanu, smothering his movement in hatred and mockery.

Codreanu writes:

“I could not define how I entered into the struggle. Probably like a man who, walking the street, with his preoccupations, his needs and his own thoughts, surprised by the fire which is consuming a house, takes off his jacket and rushes to give help to those who are the prey of flames. With the common sense of a young man of twenty or so, this is the only thing I understood in all I was seeing: that we were losing the Fatherland, that we would no longer have the Fatherland, that, with the unwitting support of the miserable, impoverished and exploited Romanian workers, the Jewish horde would sweep us away. I started with an impulse of my heart, with that instinct of defense which even the least of the worms has, not with the instinct of personal self-preservation, but of defense of the race to which I belong. This is why I have always had the feeling that the whole race rests on our shoulders, the living, and those who died for the Fatherland, and our entire future, and that the race struggles and speaks through us, that the hostile flock, however huge, in relation to this historical entity, is only a handful of human detritus which we will disperse and defeat. The individual in the framework and in the service of his race, the race in the framework and in the service of God and of the laws of the divinity: those who will understand these things will win even though they are alone. Those who will not understand will be defeated.”

This was the profession of faith that Codreanu made in 1922, at the conclusion of his university studies. As president of the National Association of Law Students, he then delineated the fundamental principles of the anti-Semitic campaign in the following terms:

“a) Identification of the Jewish spirit and mentality which have imperceptibly infiltrated the manner of thought and feeling of a significant portion of the Romanian people.

b) Our detoxification, the elimination of Judaism that has been introduced into our minds through textbooks, instructors, the theatre, and the cinema.

c) The understanding and unmasking of Israelite plans, concealed under various forms. For we have political parties led by Romanians, through whom Judaism speaks; Romanian newspapers, written by Romanians, through which the Jew and his interests speak; Romanian intellectuals who think, write, and speak in a Hebraic spirit, though in the Romanian language.”

At the same time, there stood before him the practical questions of political, national, and social order: vast stretches of Romanian land colonized exclusively by Jewish populations; Jewish control of the vital nerve centers of the principal cities; and the increasingly alarming presence of Jews in schools, where they often constituted a clear majority—an omen of a coming conquest of the professions in the generation to follow.

Codreanu also called for a simple action of unveiling. Just as in the revolutionary years, the leaders of the so-called Romanian proletarian movement were entirely Jewish, so too later, as a member of parliament, Codreanu exposed how most ministers of the Crown were bound by financial obligations to Jewish banking institutions.

At the advent of Mussolini, Codreanu recognized in him a herald of hope. He wrote, “A light bearer, who instills within us hope. He will be for us the proof that the hydra can be defeated. A proof that we can win.” He added, “But Mussolini is not anti-Semitic. You rejoice in vain,” murmured the Jewish press. “I say: the question is not why we rejoice, but why, if he is not anti-Semitic, you fear his victory and why the Jewish press throughout the world attacks him.”

Codreanu rightly saw that Judaism had achieved domination over the world through Freemasonry, and over Russia through Bolshevism. “Mussolini has destroyed communism and Freemasonry,” he wrote, “he has therefore, implicitly, declared war upon Judaism as well.” The later anti-Semitic developments in Fascist policy confirmed the accuracy of this intuition.

To bring Codreanu’s anti-Jewish worldview fully to light, one must cite the following passage from his book, in which his clarity of vision reaches an extraordinary pitch:

“Those who think that the Jews are poor unfortunates, arrived here by chance, carried by the wind, led by fate, and so on, are mistaken. All the Jews who exist on the face of the earth form a great community, bound by blood and Talmudic religion. They are parts of a truly implacable state, which has laws, plans and leaders who formulate these plans and carry them through. The whole thing is organized in the form of a so-called ‘Kehillah.’ This is why we are faced, not with isolated Jews, but with a constituted force, the Jewish community. In any of our cities or countries where a given number of Jews are gathered, a Kehillah is immediately set up, that is to say the Jewish community. This Kehillah has its leaders, its own judiciary, and so on. And it is in this small Kehillah, whether at the city or at the national level, that all the plans are formed: how to win the local politicians, the authorities; how to work one’s way into circles where it would be useful to get admitted, for example, among the magistrates, the state employees, the senior officials; these plans must be carried out to take a certain economic sector away from a Romanian’s hands; how an honest representative of an authority opposed to the Jewish interests could be eliminated; what plans to apply, when, oppressed, the population rebels and bursts in anti-Semitic movements.”

And beyond these more immediate tactics, Codreanu outlined broader, long-term strategies:

“1) They will seek to break the bonds between earth and heaven, doing their best to spread, on a large scale, atheistic and materialistic theories, degrading the Romanian people, or even just its leaders, to a people separated from God and its dead. They will kill them, not with the spear, but by cutting the roots of their spiritual life.

They will then break the links of the race with the soil, material spring of its wealth, attacking nationalism and any idea of Fatherland and homeland. Determined to succeed, they will seek to seize the press.

They will use any pretext, since in the Romanian people there are dissensions, misunderstandings, and quarrels, to divide them into as many antagonistic parties as possible.

They will seek to monopolize more and more the means of existence of Romanians.

They will systematically drive them to dissoluteness, annihilating family and moral force without forgetting to degrade and daze them through alcoholic drinks and other poisons.

And, in truth, anyone who would want to kill and conquer a race could do it by adopting this system.”

From the end of the war to the present, Codreanu’s movement has tirelessly opposed this Jewish offensive in every domain. Against the two and a half million Israelites on Romanian soil, and against all forces affiliated with or financed by Israel, the Legion of the Archangel Michael has held its line.

The scourge of political schemers, and the imperative of forging a New Man, are among the central pillars of Codreanu’s doctrine. “The type of man who lives nowadays in the Romanian political scene,” Codreanu writes, “I have already found in history: under his rule, nations died and states were destroyed.” For Codreanu, the gravest peril to the nation lay in the deformation and corruption of the pure Dacio-Romanian type, replaced by the political schemer. “This moral germ, which no longer possesses any trace of the nobleness of our race, dishonors us and kills us.”

Wherever the schemer exists, anti-national forces will find willing tools. Their intrigues, their plots, their parasitical entrenchment—all these find fertile ground in the cowardice and opportunism of such men. Long before the 1938 constitution dissolved the party system, Codreanu had already declared: “The young man who joins a political party is a traitor to his generation and to his race.”

It is not a matter of new programs, parties, or parliamentary devices. It is a matter of a new man. This vision gave rise to Codreanu’s legionarism, which is above all a school of life, the crucible for forming a new type of human being, in whom are “developed at the maximum, all the possibilities of human greatness which were sown by God in the blood of our race.”

The first organization was called The Legion of the Archangel Michael, a name that already reveals the mystical, religious, and ascetical dimension of this nationalism. For Codreanu, the formation of this higher type is the primum mobile; everything else follows naturally, irresistibly. It is through the regenerated man that the Jewish question will be resolved, that a new political form will arise, and that the fire of spiritual magnetism will awaken the masses, giving birth to victory and carrying the race onward to glory.

A defining and singular feature of Romanian legionarism is found in its organizational method—structured into nests—and in its chief aim: to create a new communal form of life rooted in strict ethical and religious criteria. That Codreanu instituted the discipline of fasting two days each week may surprise the modern observer. Yet this measure, and others like it, flow from his vision of political life as a sacred order, not a game of votes and interests. His views on prayer further confirm this orientation, seeming more proper to a monastic superior than to a political leader:

“Prayer is a decisive element of victory. Wars are won by those who have managed to attract from elsewhere, from the skies, the mysterious forces of the invisible world and to secure their support. These mysterious forces are the souls of the dead, the souls of our ancestors, who once were, like us, linked to our clods, to our furrows, who died for the defense of this land and are still linked today to it by the memory of their lives and by us, their sons, their grandsons, their great grandsons. But, above the souls of the dead, there is God. Once these forces are attracted, they are of considerable power, they defend us, they give us courage, will, all the elements necessary to victory and which make us win. They bring in panic and terror among the enemies, paralyze their activity. In the last analysis, victories do not depend only on material preparation, on the material forces of the belligerents, but on their power to secure the support of spiritual forces. The fairness and the morality of actions and the fervent, insistent call for them in the form of rite and collective prayer attract such forces.”

Elsewhere, Codreanu writes:

“If Christian mysticism and its goal, ecstasy, is the contact of man with God through a leap from human nature to divine nature, national mysticism is nothing other than the contact of man and crowds with the soul of their race through the leap which these forces make from the world of personal and material interests into the outer world of race. Not through the mind, since this anyone can do, but by living with their soul.”

Another emblematic feature of the Iron Guard is the ascetic rule imposed on its leaders. They were to abstain from the dance hall, the cinema, the theatre. They were to avoid any ostentation, even the signs of ordinary comfort. A special shock unit of ten thousand men, named in honor of Moza and Marin, two leaders fallen in Spain, was formed along the lines of an ancient knighthood. Members of this force were bound by a vow of celibacy so long as they belonged to it. No domestic or worldly attachment was to dilute their readiness to die at a moment’s notice.

Although Codreanu twice held a seat in parliament, from the very beginning he declared himself implacably opposed to democracy. To cite him directly: democracy fractures the unity of the race by generating factionalism; it is incapable of continuity in responsibility and effort; it is devoid of true authority, since it lacks the power of sanction, and it transforms the statesman into a servant of his own followers. It is the handmaid of high finance. It grants Romanian citizenship to millions of Jews.

In opposition to this, Codreanu affirmed the principle of social hierarchy and the natural selection of elites. He possessed an almost prophetic sense of the political forms destined to emerge in the epoch of reconstruction. These forms would not be rooted in democracy, nor merely in dictatorship, but in the mysterious bond between a people and its leader—as between latent force and realized power, between instinct and expression.

In this new politics, the leader is not chosen by the masses. Rather, the people recognize themselves in him, consent to him, affirm him, because his will is their own made manifest.

This principle presupposes an interior awakening, a rekindling of the soul, which begins in the leader and radiates outward through the elite. We must quote Codreanu:

“It is a new form of leadership of states, never encountered yet. I don’t know what designation it will be given, but it is a new form. I think that it is based on this state of mind, this state of high national consciousness which, sooner or later, spreads to the periphery of the national organism. It is a state of inner light. What previously slept in the souls of the people, as racial instinct, is in these moments reflected in their consciousness, creating a state of unanimous illumination, as found only in great religious experiences. This state could be rightly called a state of national oecumenicity. A people as a whole reach self-consciousness, consciousness of its meaning and its destiny in the world. In history, we have met in peoples nothing else than sparks, whereas, from this point of view, we have today permanent national phenomena. In this case, the leader is no longer a ‘boss’ who ‘does what he wants,’ who rules according to ‘his own good pleasure’: he is the expression of this invisible state of mind, the symbol of this state of consciousness. He does not do what he wants, he does what he has to do. And he is guided, not by individual interests, nor by collective ones, but instead by the interests of the eternal nation, to the consciousness of which the people have attained. In the framework of these interests and only in their framework, personal interests as well as collective ones find the highest degree of normal satisfaction.”

That such a conception does not exclude the permanence of traditional institutions is confirmed by Codreanu’s own reflections on monarchy. In his words:

“I reject republicanism. At the head of races, above the elite, there is Monarchy. Not all monarchs have been good. Monarchy, however, has always been good. The individual monarch must not be confused with the institution of Monarchy, the conclusions drawn from this would be false. There can be bad priests, but this does not mean that we can draw the conclusion that the Church must be ended and God stoned to death. There are certainly weak or bad monarchs, but we cannot renounce Monarchy. The race has a line of life. A monarch is great and good, when he stays on this line; he is petty and bad, to the extent that he moves away from this racial line of life or he opposes it. There are many lines by which a monarch can be tempted. He must set them all aside and follow the line of the race. Here is the law of Monarchy.”

If these are the central ideas of Codreanu and his Iron Guard, then the course of their struggle appears all the more tragic—indeed, nearly beyond comprehension. For a time, one might have attributed the campaign against them to unfortunate misunderstandings. But such illusions cannot be sustained. As long as a purely democratic regime prevailed in Romania, with its notorious submission to veiled powers and foreign influences, and with a monarchy that was largely ceremonial, the existence of a movement such as Codreanu’s could only provoke a desperate and unprincipled resistance. Today one pretext would be invoked, tomorrow its opposite, yet the result remained always the same: to destroy by any means the enemy who had dared to name the truth.

Codreanu’s reflections on this duplicity are bitter, and justly so:

“In 1919, 1920, and 1921, the whole Israelite press stormed the Romanian state, unleashing chaos everywhere and calling for violence against the regime, the form of government, the Church, Romanian order, the national idea, patriotism. Now, as if by magic—in 1936—the same press, led by the very same people, has become the protector of state order and legality, and declares itself ‘against violence,’ while we are branded ‘enemies of the country,’ ‘right-wing extremists,’ ‘in the pay and in the service of the enemy of Romanicity.’ Before long, we shall hear even this: that we are sponsored by the Jews.”

And he continues:

“We receive on our cheeks and on our Romanian souls sarcasm after sarcasm, slap after slap, until we find ourselves in the dreadful position where the Jews are presented as defenders of Romanicity, shielded from harm, living in tranquility and affluence, while we, the true Romanians, are hunted like rabid dogs. I have seen all this with my own eyes and endured it without respite, and it has embittered me and my comrades to the depths of our being. To rise for your country, with a soul as pure as a tear; to fight for years and years, in poverty, and in a hidden but excruciating hunger; to find yourself labeled an enemy of your nation, persecuted by Romanians, defamed as a paid foreign agent; and to see the Jewish people elevated to the role of guardians of Romanicity and of the Romanian state, which we, the youth of the nation, are accused of threatening—this is truly terrible to endure.”

These are not rhetorical flourishes. They are confirmed in the pages of his work, where the full via crucis of the Iron Guard is laid bare: arrests, slanders, trials, humiliations, persecution. Codreanu himself faced numerous trials, yet always emerged acquitted. In one case, in which he had killed, with his own hands, the murderers of his comrades, no fewer than nineteen thousand three hundred lawyers throughout the country volunteered to defend him.

Following the brief Goga experiment, it appeared that the democratic regime in Romania had come to an end and that a new, authoritarian form would emerge. From abroad, little was understood of what transpired behind this shift. Although the Iron Guard had already been dissolved, the essential conflict persisted: a concealed struggle between Codreanu and the forces that opposed his vision of the state and nation.

The Goga government was not a true alternative. It had been formed on a trial basis, with a specific tactical aim. Through Goga’s moderate nationalism and his superficial anti-Semitism, the regime hoped to divert and domesticate the rising energies that Codreanu had awakened. They offered a substitute—controlled, housebroken, easily neutralized. Yet, as Mussolini once said of Schuschnigg’s plebiscite, the experiment was dangerous, for it risked escaping the grasp of its architects.

The Romanian people did not receive the Goga government as a substitute. They received it as a signal of assent, the first wave of a rising tide. That Goga personally opposed Codreanu mattered less to them than the direction his program seemed to suggest—nationalism, anti-Semitism, a fundamental revision of Romania’s international posture. Had elections been held, Goga himself would likely have been overwhelmed by a current far stronger than he, though flowing in the same direction.

Recognizing the danger, the King intervened directly. He dissolved the democratic party system and introduced a new constitution, centralizing power in his own person. An authoritarian revolution from above, born not of the street but of the palace.

In response, the Iron Guard dissolved the movement it had recently reconstituted under the name All for Fatherland. It withdrew from the political field, not in defeat, but as a gesture of principled restraint. Its new task would be inward and spiritual: to purify, to form, to select from the masses of new adherents—many of whom had joined the Guard merely in pursuit of the Goga platform—those capable of embodying the deeper ideal.

We were in Romania at that time, and among the most serious minds in the country, there was hope for a reconciliation. The path forward, many believed, lay in a national collaboration between the new regime and legionarism. This was the view not only of Manoilescu, the foremost political theorist of the Romanian state, nor merely of those who had facilitated the King’s return to the throne, such as Nae Ionescu, but also of Argetoianu himself—the chief author of the new constitution—who said to us in conversation that such collaboration could be possible, provided that the Iron Guard renounced its prior methods.

We do not deny that, under normal conditions, when its inner force remains intact and its symbolic function is supported by fidelity and faith, Monarchy does not require any dictatorial supplement in order to fulfill its proper role. But such was no longer the case in Romania. The traditional fides had been supplanted by intrigue. The Jewish hydra had coiled itself around the vital centers of the nation. Multiparty democracy had eroded the ethical foundations and the patriotic consciousness of entire social strata.

In such a state, only a totalitarian movement of renewal can serve as the instrument of salvation. Such a movement must act as a collective force of purification, destruction, and regeneration, elevating the nation upon a new foundation of consciousness, animated by an ideal, and consecrated by a living faith. In this context, the monarchic institution, far from being overthrown, is transfigured and fulfilled. Such was the case in Italy. In like fashion, a collaboration between the new royal regime and the national-legionary movement of Codreanu would have been both possible and desirable. As we have seen, Codreanu never repudiated monarchy. He never aspired to the throne of Romania. Even his enemies did not accuse him of that.

But recent events have rendered those hopes illusory and have accelerated the descent into tragedy.

No sooner had the new constitution been proclaimed than Codreanu was once again arrested. The pretext? It was remembered, months after the fact, that he had allegedly offended a cabinet minister. Throughout his public life, under the pressure of events, Codreanu had frequently found himself compelled to speak with severity. This alone was enough.

Later came the accusation of plotting against the security of the realm. But the truth is more transparent: Codreanu’s arrest occurred immediately after the Anschluss. It is therefore highly probable that it was motivated by fear, that the victory of Austrian National Socialism might reignite the dormant fires of Romanian nationalism. Codreanu, even in silence, remained its symbol. He had to be removed.

The result was a sentence of ten years’ imprisonment, accompanied by the arrest of numerous subleaders and sympathizers of the Guard. It was evident to all that the political situation in Romania had become intensely volatile. What could not be missed was this: under the old democratic regime, when every lever of corruption had been deployed against Codreanu, the courts had still found no grounds to convict him. Yet under a so-called national and anti-democratic constitution, a sentence was passed. It was a deliberate affront to the still-living soul of the Iron Guard, now silent, now hidden, but far from extinguished.

The sentence, however, proved ambiguous. It was either too harsh or not harsh enough. For if Codreanu had indeed been guilty of treasonous conspiracy, the new constitution demanded death. But that path was not taken. They settled for ten years. Not because the crime was unclear, but because the proof was lacking.

And what they hesitated to do in the open, they would later do in the shadows.

What they did not dare to do in public at that moment, they later carried out in secret. And what could be foreseen, inevitably occurred.

After the initial moment of shock, the forces loyal to Codreanu turned to acts of vengeance. The death battalion was activated. A secret national tribunal was formed to judge and strike those deemed, from the legionary point of view, most culpable before the nation. The crisis deepened after the Prague capitulation and the Munich summit. The situation deteriorated swiftly. Arrests multiplied. One injustice led to another. The rector of Cluj University, a known adversary of the Guard, was killed. Two provincial governors were condemned to death by the tribunal, with execution set for January. The entire national atmosphere took on the air of combustible tension.

High-ranking figures, including a prince of royal blood and General Antonescu, former Minister of War under the Goga government and then commander of the Second Army Corps, were dismissed, exiled, or placed under arrest. Events unfolded with increasing rapidity, and the bitterness of both sides reached its most violent intensity. Thus we arrive at the final act of the tragedy.

On the 30th of November, a terse official communiqué announced that Codreanu, together with thirty other leading legionaries already imprisoned, had been killed by the police while attempting to escape. Their bodies were buried within three hours, almost immediately, clearly to prevent any independent inquiry into the true circumstances of their deaths.

The breaking point had been reached. The shock this provoked throughout Romania, where Codreanu’s supporters numbered in the millions, was immense. The state of siege, already in effect for other reasons, was extended to encompass the entire kingdom. The national situation entered a shadowed and uncertain phase, darker than at almost any moment in Romania’s modern history.

We have said before, and must repeat, that unless one is willing to believe that Codreanu was a man of absolute duplicity, something impossible to accept for anyone who ever spoke with him, even briefly, or who has sensed in his writings the purity, the fervor, and the profound sincerity with which he was animated, then it becomes clear that his movement was not subversive in the usual sense of the word. Its goals were not the overthrow of order, but its resurrection. They were the goals of national renewal and anti-Semitic reconstruction, of the Fascist or National Socialist type, within a framework respectful of monarchy and tradition.

And so? One is led to ask: what were the forces that caused, or at the very least contributed to, the destruction of the Iron Guard?

At the time of Codreanu’s final arrest, we were in Paris. We witnessed the delight with which the news was received in the anti-Fascist and Judeo-socialist press. It would not be excessive to say that, following the fall of Czechoslovakia, Romania was the last major zone in Eastern Central Europe still untouched by the hidden powers, those powers that operate beneath the surface of the so-called great democracies, of high finance, and of Judeo-socialism. Romania remained valuable not only for its resources, but for its strategic significance. And to such forces, pursuing their short-sighted aims through the manipulation of states and regimes, the spilling of blood, even the blood of noble and sacrificial youth, is a matter of no consequence.

Only a trifle.

End.

Chad, this is remarkable in every way! Thank you

My favorite fascist movement