What Was Once Called America

The Community Relations Service and the Architecture of Obedience

I find it both infinitely vindicating and darkly ironic that the seemingly harmlessly named Community Relations Service now stands as living proof of what for decades were dismissed as “right-wing conspiracies,” even as the deeper networks that guided it remain only partly exposed.

Established in 1964, during the socially transformative, indeed revolutionary, years of the Lyndon B. Johnson administration, the Community Relations Service formed part of the broader Great Society project that entrenched and vastly expanded the American welfare state. Created under Title X of the Civil Rights Act, it was shaped by a circle of advisers whose ideological roots reached back to the New Deal and who regarded “civil rights” not as an end in itself but as the moral and administrative foundation of what would become the Regime’s new social order. Among its architects was Benjamin Cohen, a veteran policy engineer who had served under Roosevelt and viewed the language of civil rights not as a discrete cause but as the means to a long-awaited social transformation. The statute charged the new agency to “provide assistance in resolving disputes, disagreements, or difficulties relating to discriminatory practices based on race, color, or national origin.” The words were antiseptic, clothed in moral pretense, yet they concealed an extraordinary power. The Service was placed first within the Department of Commerce, far from public scrutiny, and later transferred to the Department of Justice, where it acquired privileges and immunities that made it virtually untouchable. Its officials, known as “conciliators,” were endowed with sweeping discretion, operating without oversight, records, or accountability. From the outset it was no mere arbiter of bureaucratic routine but an instrument of social engineering, fashioned to reshape the nation under the guise of mediation.

We were told it was sheer fantasy to imagine that Washington directed demographic change, that it stage-managed the unrest which followed, that it choreographed demonstrations and pressed communities into silence. Yet this is precisely what the Service carried out, and what it even recorded with pride in its own official history. What had been mocked as paranoia by the Regime and its acolytes has in fact been revealed as policy.

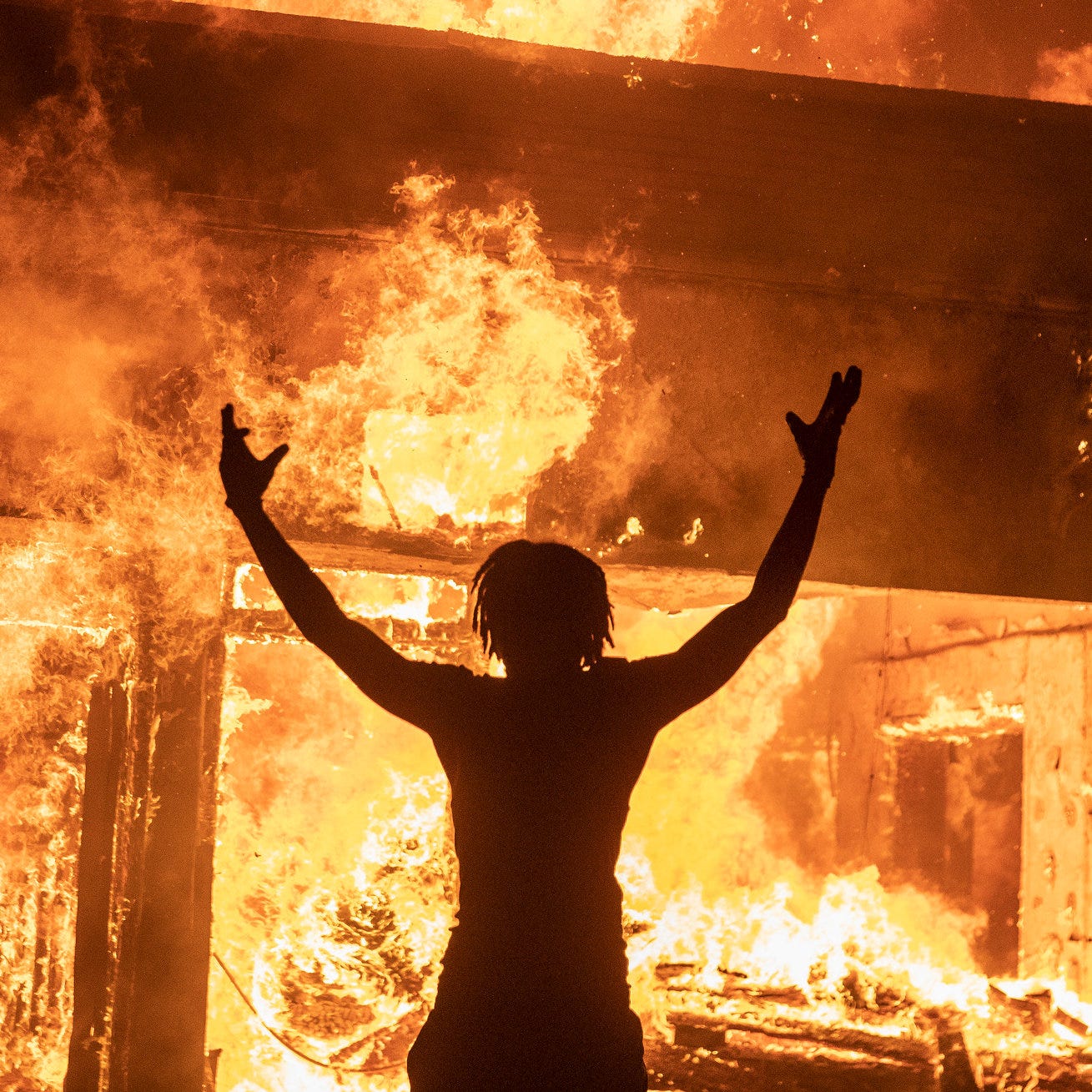

The memory of the Summer of Floyd still lingers, when cities burned and entire districts were reduced to smoke and ruin, when neighborhoods were swallowed by a kind of ritualized madness presented to the world as justice. Billions in property were destroyed, lives were overturned, and communities were left disfigured both physically and morally. The Regime’s media assured the public that this was spontaneous, an eruption of sorrow that no one could have foreseen, a convulsion of feeling rather than of intent. Yet the mark of design was visible to any who looked without illusion. The marches moved with precision, their slogans puerile yet uniform, printed in advance and distributed like campaign literature; the cameras stood ready before the first glass was broken, as though waiting for the spark to catch; the commentators spoke in the same pious cadence, as if reading from a script already approved. What was presented as outrage was in truth orchestration, the continuation of a system that had long since learned to direct disorder and to harness it for transformation.

Christopher Caldwell was right to argue that the Civil Rights Act was not reform, not the “righting of centuries of injustice,” but a revolution by other means, a rival constitution erected beside the old. Buried in its provisions was the Community Relations Service, draped in the language of conciliation and healing yet designed for enforcement. Its founders spoke without shame of preventing “backlash,” and from its first moment it carried out that mission under a veil of secrecy. Its agents, styled conciliators, were exempt from the Freedom of Information Act, their notes destroyed as a matter of policy, their officers shielded by privileges of confidentiality that could be invoked even against Congress or the courts. What was presented as reconciliation was in essence a hidden apparatus of control, a quiet but relentless mechanism for silencing those who resisted.

The record leaves little doubt. In Selma in 1965 it was CRS that arranged the march later remembered as a “moral awakening,” coordinating between federal officials, the press, and movement leaders so that the spectacle unfolded beneath its careful supervision, the images of confrontation crafted to sanctify one side and to shame the other. In Boston during the 1970s, as forced busing tore through the fabric of working-class neighborhoods, CRS placed itself between parents and authorities, not to defend the children who were attacked in the streets but to restrain the community itself from resisting. In Florida during the Trayvon Martin affair, the same methods appeared again as the agency trained local activists, coached spokesmen, and staged appearances that turned a local tragedy into a national morality play, complete with ready-made heroes, villains, and a chorus of commentators eager to confirm the script. Each episode, later remembered as a spontaneous eruption of “conscience,” was in truth the managed product of the same bureau, guided by the same logic of control and undergirded by an ever-deepening anti-White animus.

The reach of CRS extended further still. In the 1990s it was directly involved in the federal resettlement of Haitian parolees released from detention facilities following the coup in Port-au-Prince. Under the pretext of humanitarian management, the Service coordinated with the Department of Justice and the Office of Refugee Resettlement to “assist” local authorities in the absorption of these populations. Its conciliators entered small towns in Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas, urging residents to accept the placements while counseling families who had suffered break-ins and assaults to temper their words in the name of “peace.” The same pattern reappeared across the Upper Midwest, most notably in Minnesota, where Somali migration expanded rapidly under federal sponsorship. Whenever resentment threatened to rise, CRS agents descended to convene “dialogue sessions,” meeting with pastors, mayors, and school boards to preach harmony, while privately warning that open opposition could provoke federal review or the loss of funding. Families were counseled into silence, church leaders were pressed to compliance, and entire neighborhoods were transformed without consent or consultation. What was praised as peace was in truth submission, and what was described as justice was merely the quiet enforcement of obedience.

The full extent of the Service’s involvement in demographic resettlement is still coming to light, yet what evidence already exists suggests an operation far more extensive and deliberate than even its critics once imagined, one whose depth and coordination will, in time, demand a reckoning of its own. From the management of racial tension, its mandate broadened under the Regime’s later phase, during the Obama administration, into the governance of belief itself. Through the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, the Service’s jurisdiction extended beyond race into disputes involving religion, sexuality, and “gender identity.” This transformation completed what had begun with the Civil Rights Act: the conversion of a civil bureau created for “conciliation” into an organ of moral and demographic reordering. What had once intervened to suppress racial resistance now moved to regulate conviction, training police departments, advising school boards, and shaping the language of law so that dissent could be pathologized as hatred and disagreement treated as crime. Through this evolution, the logic of demographic control was joined to that of cultural re-education, and the work of government came to rest less upon persuasion than upon the careful management of emotion and belief.

For decades, every episode of unrest was met by the same process of containment. Resistance was smothered before it could ignite, and outrage was redirected into carefully managed displays of loyalty to the prevailing order. What began as the management of race relations grew into the management of the nation’s moral life, until no sphere of culture, religion, or education remained untouched. The transformation was not limited to demographics but reached into the very terms of belonging, the meaning of justice, and the boundaries of truth itself. The same methods that once silenced parents in Boston or neighbors in Minnesota had long since been absorbed into the wider machinery of governance. When White victims fell to BIPOC violence, families were pressed to temper their words and communities were counseled into silence. That same logic was carried into the cult of “gender identity,” where mutilation was hailed as progress and rebellion against nature was paraded as liberation. Even the manifestos of trans killers were suppressed when they threatened to reveal too much, locked away lest they expose the ideology through which the Regime now justifies its rule. None of this was spontaneous, nor the eruption of conscience, but the continuation of a program conceived in the mid-twentieth century, refined through decades of bureaucratic expansion, and carried forward long after the agency itself was dispersed.

The names have changed, the banners shifted, yet the directing hand endures, shaping a people taught that to question is paranoia and to resist is sin. The agency may be scattered, and as of October 2025 appears abolished or reduced to irrelevance, yet its methods remain. What it once enforced by command now survives in custom and belief, sustaining a silent order that moves unseen through every institution it once ruled openly. The structure endures though the name is gone, and the design it built still governs the destiny of the nation it remade, while the unseen hand of the Regime continues, patient and unrelenting, to guide the fading course of what was once called America.

Man, what a tough read that was.

It’s incredibly humbling to know just how insidiously and subtly these people maneuvered it all to make it seem organic. It goes even deeper than I originally anticipated.

There are people in the RW sphere that predicted that the Hart-Celler Act of 1965 was a turning point for American politics, but having read this, I find it impossible to not be equally parts distressed and glad.

On the one hand, it’s greatly unfortunate it had all led to this moment. But on the brighter side, its once strong-hand grip upon the American imagination is rapidly dwindling by the minute.

The Summer of Floyd was state-sponsored terrorism. As you point out, this terror has been an ongoing project of the Global American Empire, but I place its onset with SHELLEY v. KRAEMER in 1948, and it can be argued that it started 80 years earlier than that with Reconstruction. The United States frequently rails against state-sponsored terror all while being the world's greatest practitioner of it, more often than not targeting its own population. If we are starting to get our version of glasnost and perestroika, and the revelations about the CRS indicate this may happen, let us hope this hideous project winds down as peacefully as the Soviet Union's did (I would not bet on it even though that's the desired denouement).