The mind is not a universal given. It is a Western creation: an achievement of form, not a gift of nature. It did not emerge gradually across all peoples, nor lie dormant awaiting favorable conditions. While all humans possess the capacity for reasoning, what distinguishes the European mind is the formalization and systematization of that reasoning, particularly through introspection and self-reflection. It arose within a particular race, whose inwardness, abstraction, and metaphysical clarity gave rise to a new faculty: the power to turn thought upon itself.

In The Discovery of the Mind, Bruno Snell identifies the historical moment in which European man first came to understand himself as a subject—capable of reflection, moral judgment, and rational inquiry. This turning was neither incremental nor diffuse. It occurred first, and fully, in Greece, where the nature of the European mind found expression in a culture that elevated introspection into a principle of order.

Such a development required more than language or literacy. It demanded a fundamental shift in how man experienced the world: no longer merely as a participant in mythic cycles or subject to divine command, but as an agent with an inner life, capable of reflection and choice. The soul was no longer seen as a passive vessel, but as something that could be examined, questioned, and disciplined. The Western tradition begins not with divine revelation, nor with the administration of law, but with this internal turning. Its first triumph was not the construction of empire or the refinement of policy, but the realization of the self as a being capable of understanding and ordering its own nature.

This achievement took shape in Greece, where the inner life of man emerged from the collective forms of myth and ritual into conscious articulation. For the first time, thought could be distinguished from speech, action from instinct, and judgment from fate. The world of the heroic was not rejected, but brought under the discipline of reason. What had once been public, symbolic, and divinely mediated was now subject to individual reflection and measure.

The transformation was not immediate. In Homeric epic, the soul is expressed through emotions and actions: anger, honor, sorrow, and shame are not inward reflections but external responses to circumstance. Yet even here, the groundwork for change was laid. From the grandeur of Homer’s verse arose a new relationship between man and experience, gradually distinguishing between what is acted and what is willed, what is felt and what is understood.

Snell begins with Homer not to show the absence of the self, but to reveal its earliest differentiation. In the Iliad, Achilles does not reflect in silence; he speaks, acts, and suffers. Emotion is not concealed, but made manifest through ritual, wrath, and mourning. The soul, psyche, is not a private conceptual space but something embodied and communal. It is in the thymos—the spirited center of action and feeling—that decision and passion reside. When Homer’s heroes deliberate, they do so aloud. Their conflicts are public, and their choices are weighed by fate and divine presence.

This was not a primitive consciousness but a differentiated order in which the inner life took shape through external form. In Homer’s world, the sacred and the human remained intertwined—revealed not through introspection, but through speech and action. What later ages would internalize as private reflection was here manifest in public ritual and deed. Agency was distributed across different faculties, and identity expressed not through inward examination, but through honor, tradition, and lineage. Snell does not deny subjectivity; he locates its origin in an aristocratic mode of being, rooted in custom and made visible in form.

The Greeks did not abandon myth; they reoriented it. Through tragedy, lyric poetry, and philosophy, they began to clarify the structure of the soul. The divine was no longer an omnipresent force, but something to be discerned. The self was no longer absorbed by fate but began to confront its own choices. This shift from ritual to reflection, from narrative to principle, marked the emergence of the Western mind.

What we call introspection—the awareness of the inner self, the ability to separate judgment from desire and thought from impulse—was not a spontaneous development of mankind. It was the achievement of a distinct lineage: European man, whose biological, civilizational, and psychological nature was attuned to abstraction, hierarchy, and inner discipline. The Greek mind did not simply speculate; it sought order, gave names, and made distinctions. Its greatest strength lay not in mysticism or revelation, but in the ability to clarify what others could only feel.

The Greeks redefined the soul not as a flux of passions or a vessel of divine forces, but as a unified and structured entity. They transformed it from a receptacle of feeling into a moral and rational framework. The will was no longer viewed as divine command, and the passions were no longer confused with the self. Thought ceased to be a mere reaction to the world, becoming instead the means through which it could be understood.

This transformation could not have occurred in abstraction. It arose from a specific racial and cultural foundation, one capable of distinguishing the inner from the outer, the personal from the mythic, and principle from custom. While other peoples remained embedded in the cycle of ritual or divine mandate, the Greeks stepped outside it. They asked not only what must be done, but why, and what it meant for a man to make a choice. The emergence of the subject was not a theological postulate, but a philosophical discovery that would become the cornerstone of the Western tradition.

This mode of consciousness is not lost in later thought; it is sublimated. The passions of thymos remain, but they are gradually subjected to reasoned scrutiny. What was once expressed in action is now evaluated by judgment. The Greek trajectory is not toward disembodied rationalism, but toward unity: a soul that retains its heroic roots even as it rises to contemplate the eternal.

With the rise of lyric poetry, the collective voice of the Homeric world gives way to the personal voice. In Sappho and Archilochus, we encounter the emergence of the singular “I”—no longer a heroic speaker representing kin or gods, but a private soul expressing its joy, grief, or longing. The passions are no longer merely enacted; they are revealed. Instead of ritual and battle, we find desire, heartbreak, and satire. The self becomes capable of intimacy, inner conflict, and emotional depth. This is not yet philosophical introspection, but it is unmistakably inward.

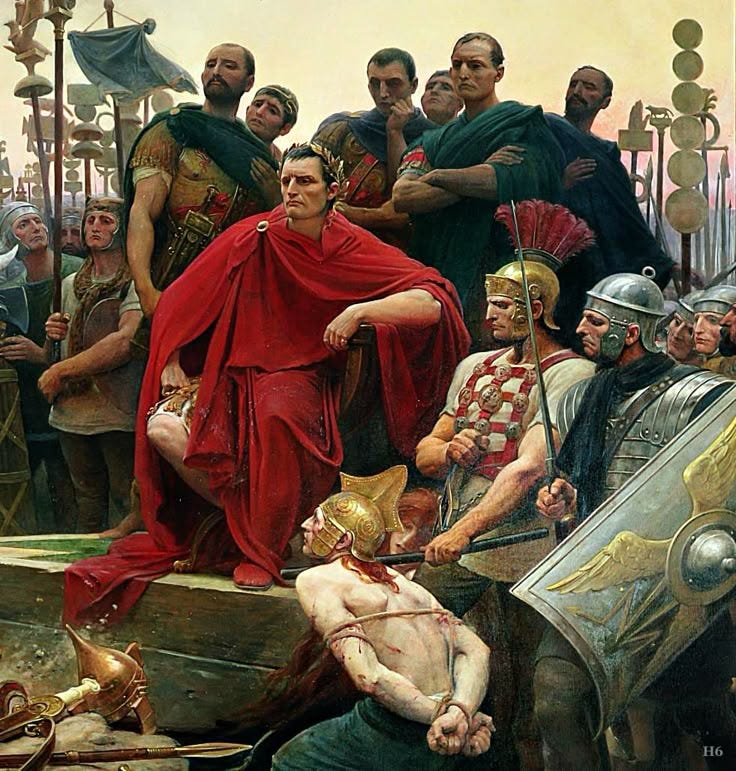

Tragedy deepens this shift. Aeschylus brings myth into dialogue with the polis, exposing divine stories to civic judgment. Fate and justice become intertwined. In Sophocles, the individual is confronted with the consequences of his own choices. The tragic hero does not merely endure the will of the gods; he grapples with the implications of his own will. Antigone, Oedipus, and Ajax—no longer just mythic figures—become agents whose suffering is fully conscious.

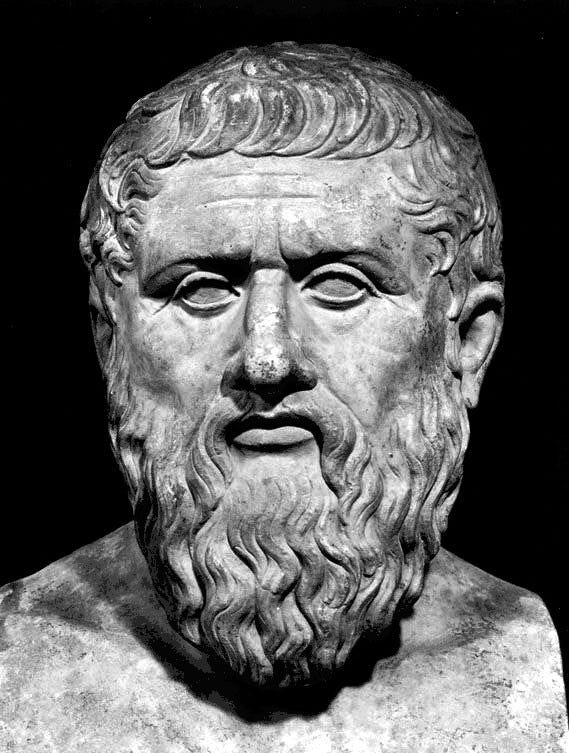

With Socrates, as presented by Plato, the final transition occurs. The moral question is no longer mythic or tragic; it becomes a personal demand. What is the good life? How should one live? These are not questions answered by appeal to custom or divine command. They require reasoned thought. In the streets of Athens, Socrates, as depicted by Plato, does not deliver doctrine. Instead, he compels his interlocutors to confront their ignorance, articulate their assumptions, and examine their souls.

The soul is no longer a stage for action or divine prompting; it becomes the site of inquiry. This is not a break from the earlier tradition but its highest refinement: the internalization of responsibility, the elevation of speech into reason, and the ordering of life through dialectic. The Greek achievement was not merely the articulation of the mind as an object, but the recognition that self-knowledge is the highest human task.

To speak of the discovery of the mind is not to trace the gradual ascent of all mankind toward universal reason, nor to suggest a diffusion of learning across cultures. It is to identify the emergence of a faculty—abstract, sovereign, and inward—that first appeared in one people: European man. The soul, as a structured and reflective whole, was not merely imagined but clarified and developed. This was not the creation of a metaphor; it was the realization of a capacity latent within a particular biological and civilizational form.

From this tradition arose the moral psychology of Plato. Building on Socratic thought, Plato envisioned justice as the harmony of appetitive, spirited, and rational elements within the soul. This development influenced the ethical rigor of the Stoics, who saw reason as the logos of the cosmos made manifest in man. It shaped Augustine’s introspective theology, where the inward turn was not for civic virtue, but to confront memory, will, and sin. The legacy of Greek thought found new expression in Descartes' cogitating subject and in the striving soul of Faust, whose relentless pursuit of knowledge and mastery epitomizes the modern crisis of reason untethered from its roots.

Snell’s thesis extends beyond the literary. It is fundamentally civilizational. The mind, as developed in Greek thought, was not a universal gift shared across time and cultures. Rather, it was the unfolding of human faculties particular to the European lineage, shaped over generations by discipline in form, measure, and introspection. It is with Plato that the mind shifts from a poetic intuition to a more definable structure. In the Republic, the soul is no longer presented as a single, undifferentiated essence, but as a composite of distinct functions: epithymia (appetite), thymos (spirit), and nous (reason). Each element plays its role, but harmony is achieved only when reason governs the whole. Justice, in this framework, is neither a social contract nor a divine command, but the internal order of the soul reflected in the order of the city.

This formulation was not a rejection of the heroic virtues of Homeric man, but their transformation. Plato did not abandon thymos; he refined it. He did not deny appetite; he placed it under the guidance of the good. The result is a vision in which the soul becomes a microcosm, reflecting the order of the cosmos. The highest part of man, nous (reason or intellect), is not merely a faculty of calculation, but the organ of truth, capable of transcending the flux and appearance of the material world to contemplate the eternal Idea of the Good.

In this ascent, the Greek conception of inwardness reaches a critical point. The divine is no longer seen as a chaotic force of unpredictable gods but as the standard of truth and intelligibility. Man, no longer passive to fate, becomes a being capable of aligning his soul with what is enduring and real. This is not introspection driven by psychological curiosity, nor is reason merely a technical tool. It represents a form of metaphysical integration—a vision of wholeness, revealed through the clarity of a mind shaped by discipline and order.

The Socratic life, as presented by Plato, is not defined by conformity or obedience, but by constant self-examination. To live well is to think rightly: to orient the soul toward truth, rather than mere custom, and to structure one’s life around what is permanent, not what is permitted. This ethos does not reject the divine but refines it. The gods of myth give way to the agathon—the Good itself, no longer personified but understood as a principle, not approached through sacrifice but through contemplation.

This shift transforms the religious and moral landscape of antiquity. Ritual appeasement is replaced by philosophical inquiry, and divine command is supplanted by ethical deliberation. Where the sacred was once external and inherited, it becomes internal and intelligible. The soul becomes the site of struggle, not just against temptation but in the pursuit of clarity. In that clarity, conscience is born, not merely as a social restraint, but as an inner measure: the capacity to recognize what is good and act in accordance with it.

Here, inwardness is no longer an emergent property of poetry or law, but the very foundation of moral life. Man must interrogate his actions, scrutinize his motives, and weigh his desires—not merely to conform to external rules, but to align himself with the intelligible structure of reality. This is the true inheritance of Greek philosophy: not a method, but a mode of being. Thought becomes the path, and the soul its terrain. What Snell reveals, therefore, is not the primitive stirrings of modern rationalism, but the elevation of man through ordered self-rule. The Greek mind, at its peak, is not fragmented, reactive, or abstract in the modern sense. It is structured, measured, and consciously directed toward the integration of inner life with outer order. The unity it sought was not mechanical, but organic—a harmony of the soul with itself, of the soul with the polis, and of both with the cosmos.

This unity was not achieved through doctrine alone. It required a people whose temperament was suited to such integration. The inward clarity of Greek thought was inseparable from the character of the men who produced it: aristocratic in bearing, attuned to proportion, and disciplined in form. The mind, in this sense, was not a disembodied tool but the expression of a particular anthropological type, one capable of translating experience into principle and shaping life in accordance with that principle.

What emerged in Athens was not only a philosophical breakthrough but a civilizational orientation. A new mode of man appeared: not merely aware of the world, but aware of himself within it; capable not only of choosing, but of justifying his choices; able not only to act, but to account for his actions. It was from this form that Western civilization would derive its moral and intellectual foundation.

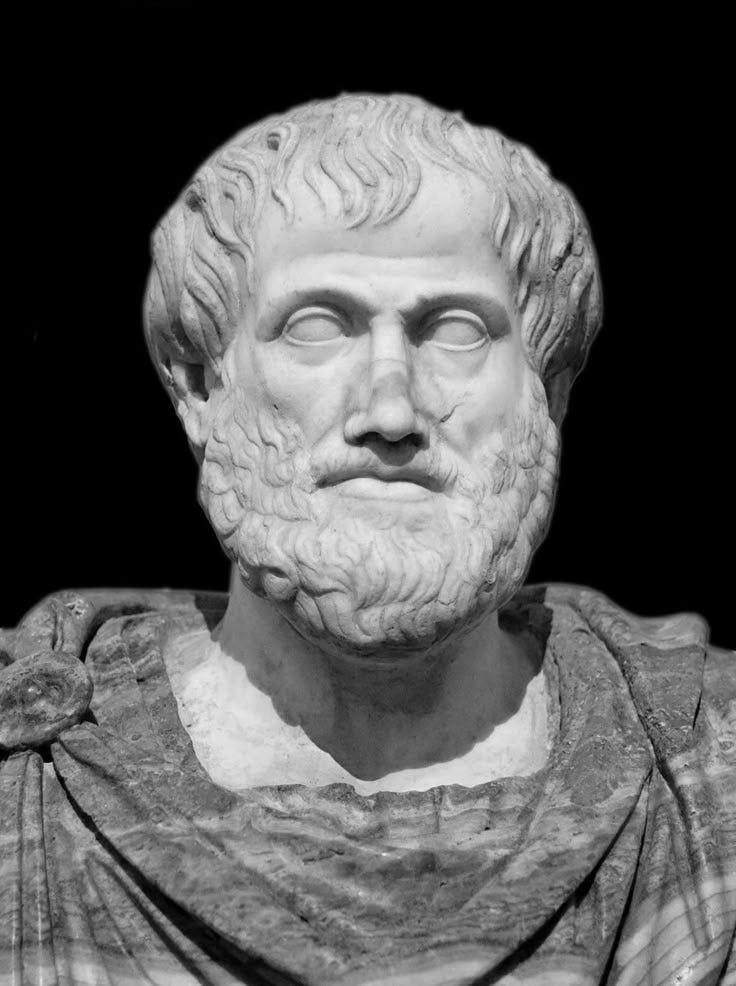

Aristotle brings this legacy to its fullest articulation. In the De Anima, the soul is no longer viewed as a poetic force or a battlefield of divine impulses, but as a structured hierarchy of capacities. It is analyzed not through metaphor, but according to nature. The nutritive soul, shared with plants, governs growth and sustenance; the sensitive soul, shared with animals, enables perception and movement; the appetitive and perceptive faculties allow for desire and sensation. Yet above these stands the rational soul, nous, which alone perceives causes, weighs ends, and acts in accordance with principle.

This hierarchy does not reduce man to mere components; it reveals the form in which his being is completed. In its highest function, as nous poietikos (the active intellect), reason transcends the individual and participates in the divine. In this state, thinking is not a mechanical process, but a form of communion with the intelligible structure of reality.

For Aristotle, to think rightly is to live rightly. The intellect is not a private faculty, but the means by which man aligns himself with the order of things. The good life is not the result of appetite or convention, but the harmonious actualization of one’s nature. Virtue is not found in suppressing the passions, but in ruling them in accordance with reason. Happiness, eudaimonia, is not the pursuit of pleasure, but the fulfillment of one’s form.

This culmination is not the product of concept alone. It reflects an anthropological foundation, without which no such articulation could have emerged. The Greek ability to define and order the soul—to distinguish between faculties, name their operations, and arrange them in a hierarchy of ends—presupposes a particular type of man: aristocratic, restrained, conscious of proportion and measure, inwardly stable, yet attuned to form. The philosophical achievement of Greece was not an accident of climate or circumstance, nor a cultural abstraction detached from biology. It arose from a people whose nature inclined them toward reflection, self-command, and metaphysical inquiry.

What Aristotle presents in system, Homer evokes in symbol, and Plato refines in dialectic. Yet all three are expressions of a single lineage—one that viewed man not as a vessel for divine will, nor as a creature of instinct alone, but as a being capable of knowing himself and ordering his life accordingly. The discovery of the soul’s structure was not a dissection, but a realization—of form, measure, and a higher vocation.

The mind the Greeks discovered did not perish with the decline of the polis; it endured through transformation. Preserved in the works of Plato and Aristotle, it passed into Rome, where it was absorbed into legal reasoning and Stoic moral order. With the Christianization of the empire, it was reshaped by Augustine, who turned its focus inward, not for civic virtue or philosophical harmony, but to confront memory, guilt, and the hunger for grace. Noverim me, noverim te—“let me know myself, let me know Thee.” In Augustine, the Platonic ascent became confessional. The soul was no longer just a rational structure, but a terrain of sin and salvation. Introspection deepened into repentance; the mind became a witness not only to form but to fallenness.

This passage into the Christian era did not sever the Greek root; it transfigured it. Reason, once the crown of the philosopher, became the image of God within man. The inner life became a site of moral struggle and divine encounter. The soul remained structured, ordered, and knowable, but its ultimate end was no longer the contemplation of the Good as such, but reunion with the Creator. The logos did not disappear; it was reoriented, made to serve a different final cause, yet it remained the same faculty, the same inward power.

In Aquinas, this union of Greek form and Christian end reaches its most systematic expression. Drawing upon Aristotle’s De Anima, Aquinas preserves the architecture of the soul—its vegetative, sensitive, and rational powers—but situates them within a divine teleology. The rational faculty, nous, is not negated by revelation; it is perfected by it. Reason becomes the handmaid of theology, rather than its adversary. The mind remains the central faculty by which man knows reality, now elevated to contemplate not only the natural order but the Creator who sustains it.

Aquinas affirms that grace does not abolish nature but completes it. The virtues remain intelligible, and the soul retains its structure. To act justly is still to subordinate appetite to reason, and to think rightly is to align oneself with an intelligible order. Even though the highest truths now surpass human reason, the path to them remains rational. Theology does not replace philosophy; it builds upon it. The mind, far from being diminished by faith, is entrusted with its highest task: to know God through what can be known, and to assent where reason yields to mystery.

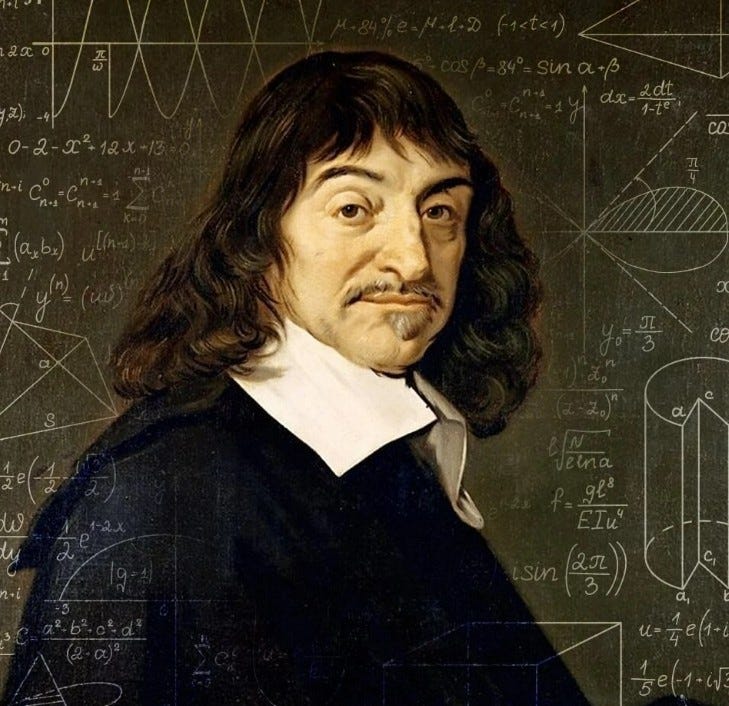

With Descartes, the inward turn of the Western mind undergoes a fundamental inversion. Reason is no longer a faculty harmonized with nature or directed toward divine truth. It becomes the sole foundation of certainty in a world stripped of inherited meaning. Cogito, ergo sum—“I think, therefore I am”—signals not the culmination of Greek rationalism, but its radical reduction. The soul is no longer an ordered whole within a moral cosmos; it becomes an autonomous subject confronting an external world through doubt. Descartes does not begin with being; he begins with negation. All tradition, all sense experience, all authority is suspended, leaving thought itself as the unshakable ground of knowledge.

This shift marks the emergence of the modern self: abstract, detached, and self-grounding. What the Greeks approached through harmony, discipline, and ascent, Descartes reinterprets as interior certainty. The nous is no longer contemplative; it becomes methodical. Thought transforms into calculation, precision, and technique. The soul loses its moral and cosmic dimensions, now recast as the guarantor of a rational order built from the inside out. In this transformation, the Western mind does not expand; it narrows, collapsing metaphysics into epistemology and reducing the search for truth to a system of proof.

Yet this triumph of autonomous reason concealed a deeper fracture. Separated from nature, severed from tradition, and detached from any given order of being, the modern mind began to disintegrate. Rationalism, having declared itself the sole foundation of truth, collapsed under the weight of its own absolutism. Skepticism followed. The thinking subject, once the bearer of knowledge and moral clarity, became opaque, unstable, and ultimately dispensable. What had long been understood as the psyche or soul was redefined by mechanism and impulse. Psychology supplanted moral philosophy, and neurology displaced the intellect. The mind itself, once revered as the divine faculty, was reduced to an emergent property of matter: measurable, predictable, and programmable.

What replaced the nous was not reason, but system. Contemplation gave way to information, memory to stimulation, and moral discipline to subjective preference. The sacred interiority, cultivated through centuries of philosophical and religious reflection, was hollowed out and repurposed for utility. The soul was no longer a site of judgment, hierarchy, or transcendence, but an instrument of desire, consumption, and response. In abandoning the mind as vocation, modernity did not liberate man; it dismantled the very form that had once allowed him to know himself.

This dissolution was not the result of historical accident or technological advancement. It was an act of volition—a relinquishment of form, memory, and duty. A civilization cannot sustain a conception of freedom it no longer understands. The Greek discovery of the mind was not merely the recognition that man possesses reason, but the understanding that he is called to use it—to govern himself and to measure his life not by appetite or impulse, but by the truth of things. The mind was not a function of the body; it was a summons: to recollection, to form, to alignment with what is higher than the self.

To think rightly was not a neutral process. It required moral seriousness, intellectual discipline, and an education in speech and measure. The mind, as conceived in the classical tradition, did not emerge spontaneously. It developed through poetry and philosophy, tragedy and law, and through generations of cultivated order. The Greeks did not discover the mind as one might uncover a physical property. They brought it into being through sustained effort, by naming, distinguishing, and harmonizing the soul's powers in accordance with nature and truth.

Bruno Snell did not merely trace a literary evolution or document the gradual interiorization of experience. He recorded the emergence of a particular human type: inward, deliberate, capable of self-mastery and reflective judgment. This figure, first glimpsed in the Athenian philosopher, later transfigured in the Christian theologian, and ultimately recast as the modern subject, was not an abstract ideal, but the embodiment of a civilizational inheritance. What emerged through Greek literature and philosophy was not a universal mode of consciousness, but the structured soul of European man: differentiated, ordered, and attuned to principle.

This soul did not arise in abstraction. It was forged within the city, tempered by law, measured by poetry, tested in tragedy, and perfected in reason. The ability to reflect and act according to form, rather than impulse, required a people whose nature could sustain such a task across generations. What Snell illuminated was not merely a cultural development, but the manifestation of an inward configuration shaped by racial and historical depth. The mind, in this sense, was no philosophical accident. It was the spiritual expression of a people whose vocation was self-knowledge.

Its continuity was never assured. The mind, as it came to be known in the West, was summoned into being by European man, whose disposition favored inwardness, clarity, and metaphysical order. To endure, it required education, cultural formation, and philosophical defense. It depended on hierarchy, language, and deliberate transmission. Though it may be forgotten or misused, each genuine act of reflection still bears the imprint of those who first gave it form.

The survival of this legacy will not be determined by institutions, which have long since abandoned their role as guardians of our ancestral patrimony. Nor will it be secured by technology, which now empties the very interior it once promised to refine. Instead, it rests with those capable of sustaining the tension between form and self, those who remember. The Greeks discovered the mind, but it belongs to those who continue its discipline: not merely to think, but to think well, in accordance with what is. This is not a universal vocation. It is the burden and the glory of European man.

Sidenote:Top 3 hellenics?

For me its

1. Heraclitus

2.Thucydides

3.Aristotle

It is a rather tiresome western fantasy that discursive reasoning and philosophical thought originated in Greece as 6 schools of philosophy ,including materialist, idealist,epistemological , metaphysical, atomistic, moral and other systems, originated between 1000-500BCE in India.

The less comprehensive Greek systems originated between 700-400 BCE